|

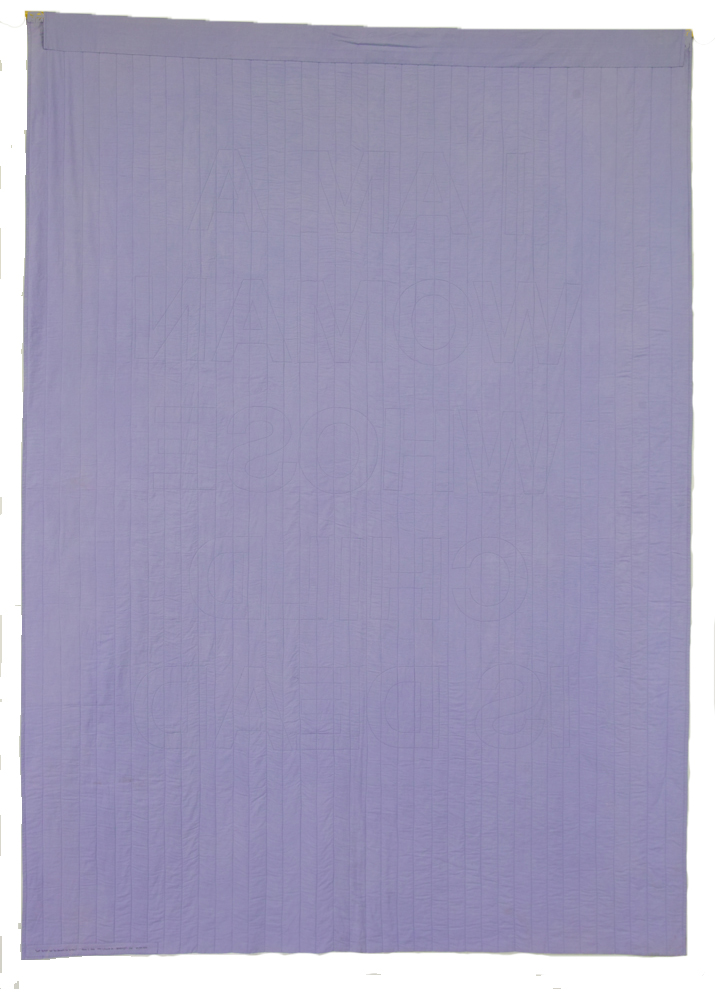

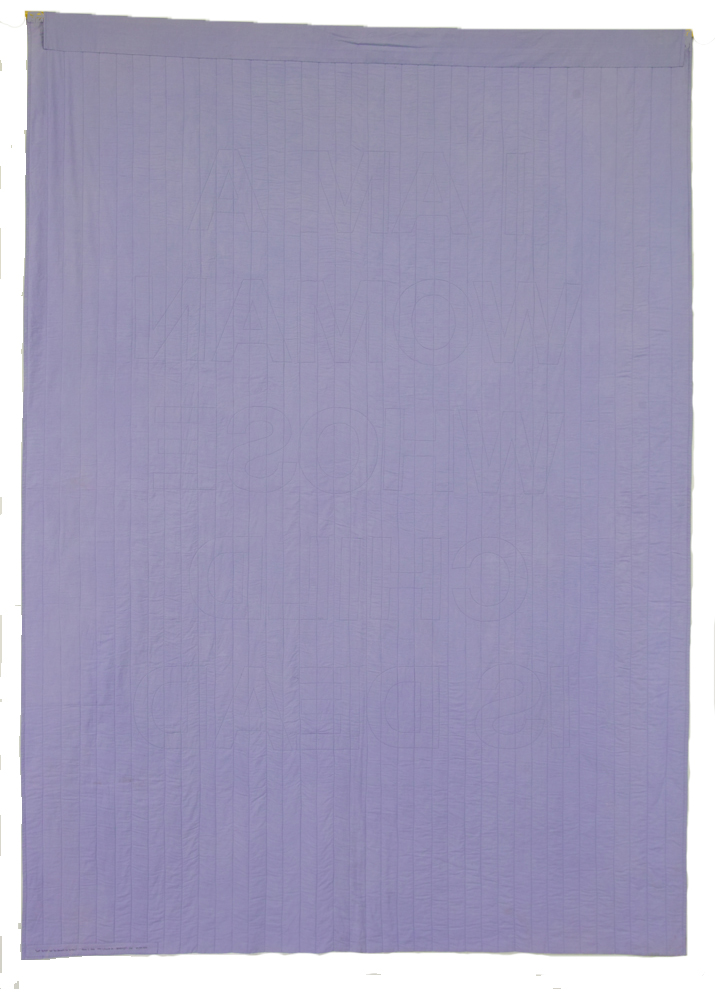

front

|

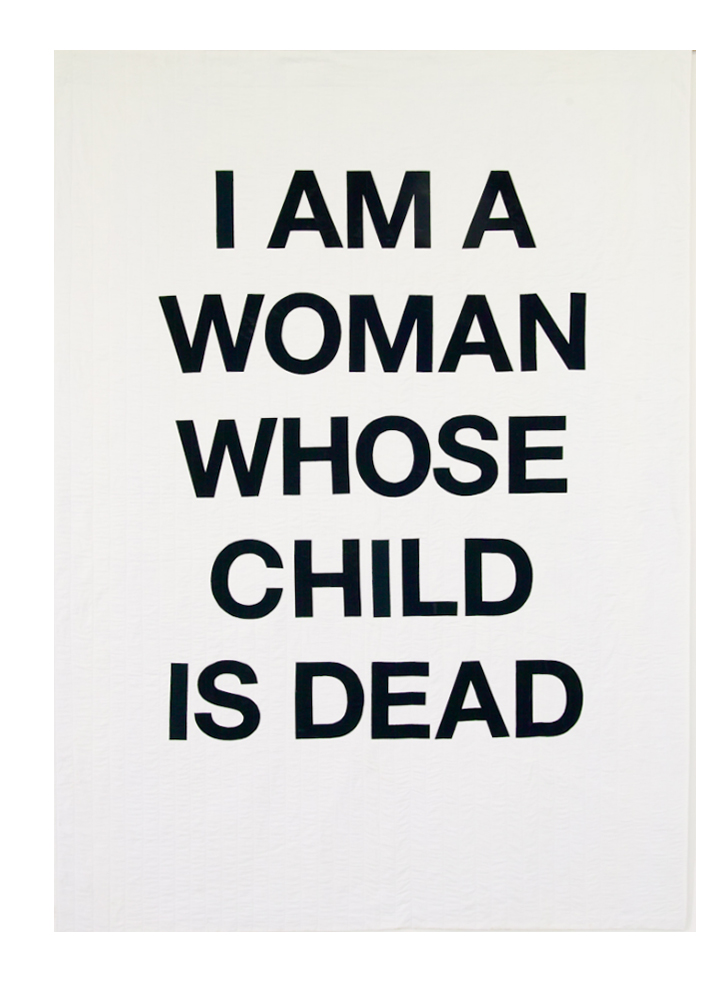

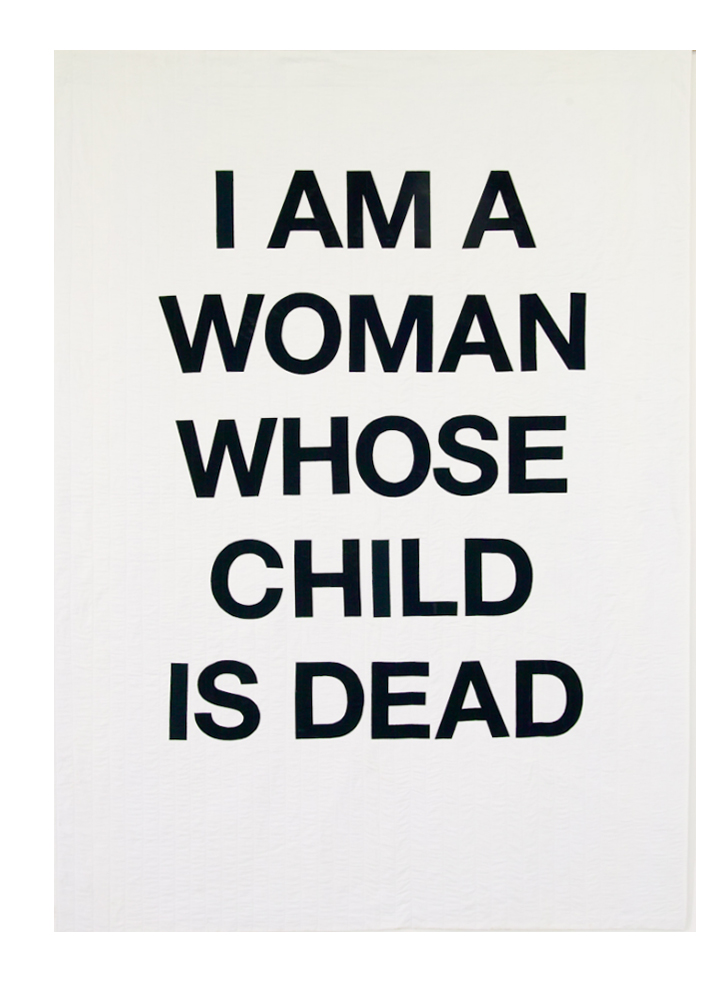

back

|

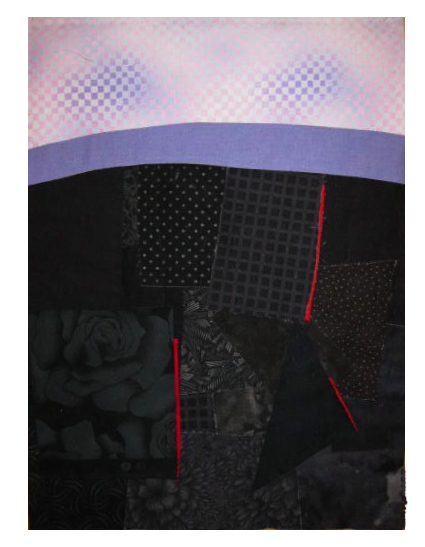

self-Portrait,

year

2: Beneath the surface

(2014)

Hand-dyed

cotton,

fused, felt batting, machine quilted

68

x 94 inches

The

idea for this quilt goes back to

2005/06, during the second year after Jeremy died. People expect that

the first

year after the death of a loved one it will be very difficult; but after

a

year, moving through one marker after another until the anniversary

arrives,

the expectation is that things will ease up. Indeed, that was my own

experience

after the death of both my parents in the winter of 2003. By the summer

of

2004, I was feeling I could get back to the normal run of life. But then

Jeremy

died. A year passed, and still, the loss continued to dominate my inner

life.

I

carried out daily life, as one has to

do. I taught my classes, attended meetings, laughed at jokes, and

responded to

friends. From the outside, the loss was invisible. But on the inside, I

continued to be shaped by loss, grief, and regret. In an early attempt

to

express this feeling of disjunction between outer appearance and inner

condition, I made a small maquette that put it in abstract form: a field

of

black patches in the bottom two-thirds of the rectangle, a lighter field

at the

top, and the two separated with a narrow band of lavender fabric that

represented my external appearance of equanimity.

Only

after choosing the color for the band did I learn from a friend

that lavender was the Victorian color of mourning, allowed after black

had been

worn for a period of time. A sliver of red was inserted in the black

field,

representing the stab of anguish that can surface without warning. I

liked this

design, but did not feel a push to take it further into the making of an

actual

quilt.

I

pursued another path, connected to the

memory of the yellowish mud that covered Jeremy’s body after the

accident, a

memory that haunted me. I looked for fabric just that color, and after I

learned to dye fabric, dyed many samples until I settled upon the hue

close to

my memory. In parallel, I thought about a statement that would reflect

how my

identity had changed since the loss of my son. I ended up with “I am a

woman whose

child is dead.” I searched for ways to inscribe the message in an

obscured way,

representing its invisibility to others.

An

early plan was to appliqué large

letters of the same fabric onto the mud-colored background; I also did

trials

just stitching letter patterns in the same color thread. At one point,

in 2012,

I was talking through the project with Bill Kerr. “I’ve been working on

how to

make the words only slightly visible,” I said to Bill, “to represent how

invisible my state of agitation is to everyone around me. But sometimes

I think

the quilt should scream out how I feel—that I should proclaim it in bold

black

and white.” “Maybe you should make two quilts,” said Bill. These simple

words

of insight and affirmation were key to the development of the quilt. As

Bill

and I talked, we developed the idea of making two quilts, with the

intent to

show them at an exhibition in such a way that the “hidden message” quilt

would

be seen first, and then afterwards the bold quilt. I eventually changed

the

color of the first quilt from mud to lavender, pulling in the color from

the

strip of lavender in the earlier maquette. I dyed several versions of

lavender,

until I came up with precisely the dusky lavender that I had in my mind.

I also

moved from the idea of two quilts to one double-sided quilt, which was

completed in 2014. The mud colored fabric was transferred to a quilt

devoted to

the accident itself (Accident).

I

have shown this quilt in two other

settings. In both cases, the quilt was shown with the black/white side

forward.

I am grateful for this opportunity to show the quilt as I originally

intended.

If you look closely, the words are just barely visible on the lavender

side as

the stitching around the letters on the other side.

The fact that they are faint, and also

backwards, is a way of representing that the loss persists in the second

year

(and beyond), but it is difficult to perceive from the outside.

You have to be very close to see it. . .

This

was a technically challenging quilt

to make. Often, a final piece looks simple in design but is the result

of many

decisions on multiple fronts. Choosing what font to use for the message

was one

such decision. I am very satisfied with my final choice (Helvetica Neue

Bold),

but it came only after many weeks of trying out various fonts, reading

about

typography in general, and about Helvetica in particular. The size of

font to

use was another decision, and then figuring out how to print out letter

templates

that large. Tim Stedman of the Knox College Art Department and Bill Kerr

helped

with all things typographical.

How

to lay out the eight words of the

message was another decision. Should it be horizontal like a billboard,

which I

had in mind when choosing Helvetica; or should it be vertical? I chose

vertical

because it is closer to the human figure, and I think of this as a

self-portrait. I also had to decide how many lines the message would be,

and

where the line breaks would fall. Many versions were printed out in

small

format on the computer until I came up with the one that felt best to

me. I

enjoy hand appliqué, and assumed I would use that for fixing the letters

to the

background, but I decided that crisp edges and corners were more

important than

the pleasure of handwork, so I fused on the letters instead. I tried out

horizontal quilting lines, but decided on vertical, and then tried out

various

spacing for the vertical lines. I ended up with spacing just a little

narrower

than the width of the letter elements. I also tried out various

battings,

ending up with a layer of felt for the batting, as I wanted the quilt to

be

very flat.

When

this quilt was shown in 2015 at

QuiltCon (a national show for modern quilting), it created a stir,

leading to

two published interviews with me and many postings on social media.

I was humbled by the response, and gratified

to know that my work could touch others deeply--both those who have

suffered

deep loss themselves, and those who haven't, but who appreciate this

glimpse

into the world of loss.

I

look back through my notes and samples,

done over a period of nine years, and marvel at the idea’s

permutations. The

measure of the quilt’s success for me is looking at it and knowing I

would not

change anything.