FROM STUDY TO STUDIO:

MEANING AND MOTIVATION IN SCHOLARSHIP AND ART

Penny S. Gold

Presentation in the "Friday at Four" series of faculty work in progress

Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois

April 30, 2010

For many years, this desk was the focal point of my study, the place

where I wrote books, where I did my scholarship. My laptop sat on

the pull-out typing return. Detailed chapter outlines were tacked

to the bulletin board. The room was filled with books and files

connected to my job, to my professional life. It was a good place

to work. Thirty-plus years produced, among other things, these

four books:

In the summer of 2005, I abandoned work on a fifth book, and I

dismantled the study. I took out all the books and files. I

emptied the desk. I moved in my sewing machine, fabric, thread,

and tools. I changed my study to a studio. The words come

from the same Latin root, meaning "to pursue eagerly." Yes, I

pursued scholarship eagerly for over thirty years. Now that same

eagerness is going into the making of art. This is the story of

how scholarship came to have a central place in my life, why I stopped

doing research, and how I came to do something else. It's

not easy for me to tell this story publicly, but in this setting of the

community that has given me so much support along the way, I find

myself wanting to explain what happened to me.

I was an indifferent student through most of college. But in the

fall of my senior year, I happened into a medieval history class, along

with another on the history of culture and a third on cultural

anthropology. I was hooked. I quickly applied to graduate

school, but I had no idea what I was in for. I had never done a

significant research paper and knew nothing about professional

scholarship. I was interested in what medieval people wrote, not

in what modern scholars wrote about them. My first graduate

courses were a rude awakening to professional training. But

happily, I discovered the key to making scholarship a meaningful

endeavor for me—which was to choose a research question that

connected up with concerns in my personal life. This way, the

research really mattered to me—I was highly motivated to find

answers to the questions I posed. And so was launched the

research that occupied me for a dozen years, through the dissertation

and the book that followed, The Lady and the Virgin: Image, Attitude, and Experience in Twelfth Century France, the topic of women

in twelfth-century France reflecting my deep involvement in the women's

movement of the 1970s. This book is still in print after 25

years, and still being cited. My other

major work of scholarship, Making the Bible Modern: Children's Bibles and Jewish Education in Twentieth-Century America, looked at the

production and use of children's Bibles in Jewish education in

twentieth-century America, a project that helped me figure out

issues of Jewish identity in the modern world and about the education

of Jewish children, issues in which I was also engaged on a personal

level. In both books, the central question took me far afield to

find answers.

In both these books, I took a cultural practice and examined

multiple contexts that could help make sense of it. For the Bible

project, I not only pored over the dozens of Bible story books for

Jewish children, but also read deeply in the history of public

education in America, Protestant religious education, the ideology of

democracy between the wars, narrative theory, children's literature,

the history of biblical interpretation and of Jewish education, and the

development of Reform Judaism. I loved this process of exploring,

pushing boundaries, persisting until I could put together enough pieces

of the contextual puzzle that I could say, "now I understand it."

Now I'm going to back up and give you a parallel account of the place in my life of making things.

I have loved making things since I was a child, mostly needlework of

one sort or another, beginning with knitting a doll blanket. I

learned knitting, sewing, crocheting, embroidery--all from my

mother. It was a large part of my relationship to her.

Knitting has been the mainstay.

Why have I knit all these years? I enjoy the feel of

knitting--the repetitive motion, the contact with the yarn, the

satisfaction of seeing a garment or afghan grow from the work of my

hands. Most of what I knit is done in a very simple stitch so

that I don't have to look at the work, allowing me to knit in

situations where my attention needs to be directed elsewhere, as shown

in this photo taken at a city council meeting.

The results of the knitting are gratifying too, providing hand-made

gifts for many people in my life. I rarely knit for myself.

For most of my life, I never gave any thought to quilting. It was

not something my mother did, and learning from her was how I learned

needlework. But in the spring of 2001, Rick Ortner's young

daughter Katie, whom I had previously taught to knit and sew, asked if

I could teach her to quilt. (Rick was a long-time member of the

art faculty at Knox, leaving here in 2003.) Spurred by Katie's

interest, I checked out a pile of books from the public library and

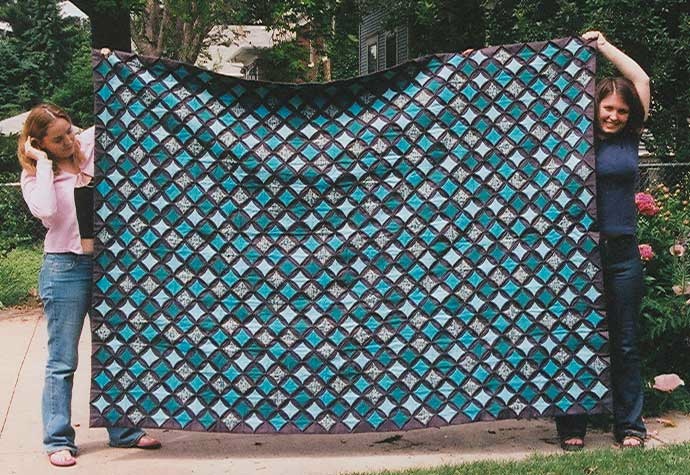

learned enough to begin. Katie and I together made this quilt, a

pattern called Cathedral Window.

(Holding the quilt are two Knox quilters, Claire Rasmussen and Claire Leeds, both '03.)

I found I enjoyed quilting and set about learning various techniques,

which I did by making a succession of small projects, first potholders,

then placemats, and on to small wall-hangings.

Much as I was enjoying this new hobby, I was also frustrated by the

greater challenges presented by quilting. The challenge is

this: there are many, many more choices to make in

quilting. In knitting, I'd choose a pattern, select a color from

the limited range of yarns available, and follow the directions.

In quilting there are choices to make every step of the way, even when

using a pattern. While my ability to use color, value, and shape

improved through the many small projects, I was very aware of how much

I did not know about design, especially color and composition.

In 2004, I had enough confidence to undertake a bed-sized quilt—a

quilt for my son to take with him to college. We chose a log

cabin design, in his favorite color, blue. These are some of the blocks.

Jeremy was to

begin college in the fall of 2004, and I wanted the quilt finished by

then. I had almost all the blocks done by the beginning of the

summer.

And then Jeremy died.

For a week or so, the dark chasm that loomed on all sides was kept at

bay by the round-the-clock presence of family and friends. But

then one has to step back into the routine of life, and I found this

very difficult. Because it was summer and I wasn't teaching, my

days were unstructured by work. The scholarly research I had

planned to do was of no interest to me. Reading, which had always

been such a large part of my life, was also of no interest. One day it

occurred to me that sewing might help me pass the time—the days

were so long. I went over to the corner where I kept various

projects, and found some small appliqué blocks that I had

entirely forgotten about, all set to be sewn. It

turned out this was just what I needed to help me through the

day.

The soft colors, simple shapes, and the hand-sewing itself

were calming, and they kept my mind occupied in a way that helped keep

at bay images of Jeremy's accident and of his dead body.

The blocks were quickly finished, but I needed another project like

this. The sewing was a kind of analgesic, almost an anesthetic. I lined up another project, this

time going even further into the hypnotic effect of repetition by

sewing again and again just one simple shape, a circle (about 47"x65").

With these projects, the reason I was quilting had changed. It

was not just a pleasurable pastime, resulting in gifts for friends, but

something I needed to do for my sanity, that I needed to do to get

through each day. And the resulting quilts were no longer

something I could give away. I needed them by me.

As I worked on the simple appliqué

pieces, I also considered what to do about the log cabin quilt I had

been making for Jeremy. How could I finish it, now that he was no

longer here to receive it? But how could I discard this quilt I

had been making for him? I finally thought of a way that I could

finish it, but embed in it my grief over his death. At the time

Jeremy died, I had only three blocks left to complete the forty-eight

that would make up the top. I

decided to change the design for the last three blocks, making them off

of a five-sided center, rather than off the four sides of a

square. When set into the diamond pattern Jeremy had chosen for

the layout of the blocks, the placement of the three final blocks

expressed for me the way in which his life had so abruptly gone off

course. I thought a lot about where to put the three blocks. I

put them together rather

than scattered through the quilt; towards the edge rather than in the

center; towards the bottom rather than the top; catching one's vision,

but not dominant.

At this point, I'm going to shift back to what was happening in my

scholarship—going back past July 2004 when Jeremy died, to the

winter of 2003, when I was in the final stages of completing my book

Making the Bible Modern. In mid-March 2003, the copy-edited

manuscript of this book arrived in the mail, with a deadline of three

weeks for final edits. My mother, in a nursing home here in

Galesburg, was in the very final days of her life, dying from lung

cancer. My father had died just three weeks before, after a long

decline from Alzheimer's. The press was understanding and

generous in their extension of the deadline, but if the book was to be

published, the task could not wait long. A month after my

mother's death, I picked up the manuscript again. Working out the final

nuances of prose gave me none of the usual pleasure. I wanted my

parents back and the book dead—this is how I felt.

Would there be another book after this one? I had been jotting

down ideas and gathering references for a next book since mid-way

through the book on Bible stories, and I had loved the feeling of a

book quietly developing in the background while another was on the

front burner. But with the index for Making the Bible Modern

completed in the fall of 2003, some months after the deaths of my

parents, I found I had no drive to begin a new project. Then, as

more time passed, and a sabbatical approached, it slowly seemed

possible that I might try again. So there it stood on my to-do

list for summer 2004—to go through the box of notes and

references I had accumulated, and see where it might take me.

And then Jeremy died. In the wake of his death, scholarly writing

left my life. The kinds of questions that fuel research and that are

answered through scholarly writing were no longer part of my mental

activity. I think scholarly work also became bound up in the

guilt inevitably felt by a parent whose child had died. All those

occasions I'd gone to conferences or been at my desk, instead of being

with Jeremy.

I returned to teaching, but not to scholarship. As Roger

Rosenblatt wrote, after the sudden death of his daughter: "I

found I could not write and didn't want to. I could teach,

however, and it helped me feel useful." Much of my time at

home was spent quilting—projects like the ones I've shown

you. Then my life took another turn, as the result of a workshop

I attended in June 2005. Most quilting workshops focus on

technique, with students replicating a quilt designed by the

teacher. In contrast, this was a week-long design workshop for

quilters. The teachers, Bill Kerr and Weeks Ringle, taught a

design process, not a specific technique or pattern. My hope was

that learning more about design principles would help me with the

innumerable choices of quilting.

To prepare for the workshop, we were supposed to come with three

possible ideas—memories of events, things we'd like to do in the

future. These prompts didn't work for me, so I turned to

something else of interest—the late winter Midwestern landscape.

But then it was June, Design Camp was a week away, and I realized I was

bringing with me only one idea, not the three they had asked for.

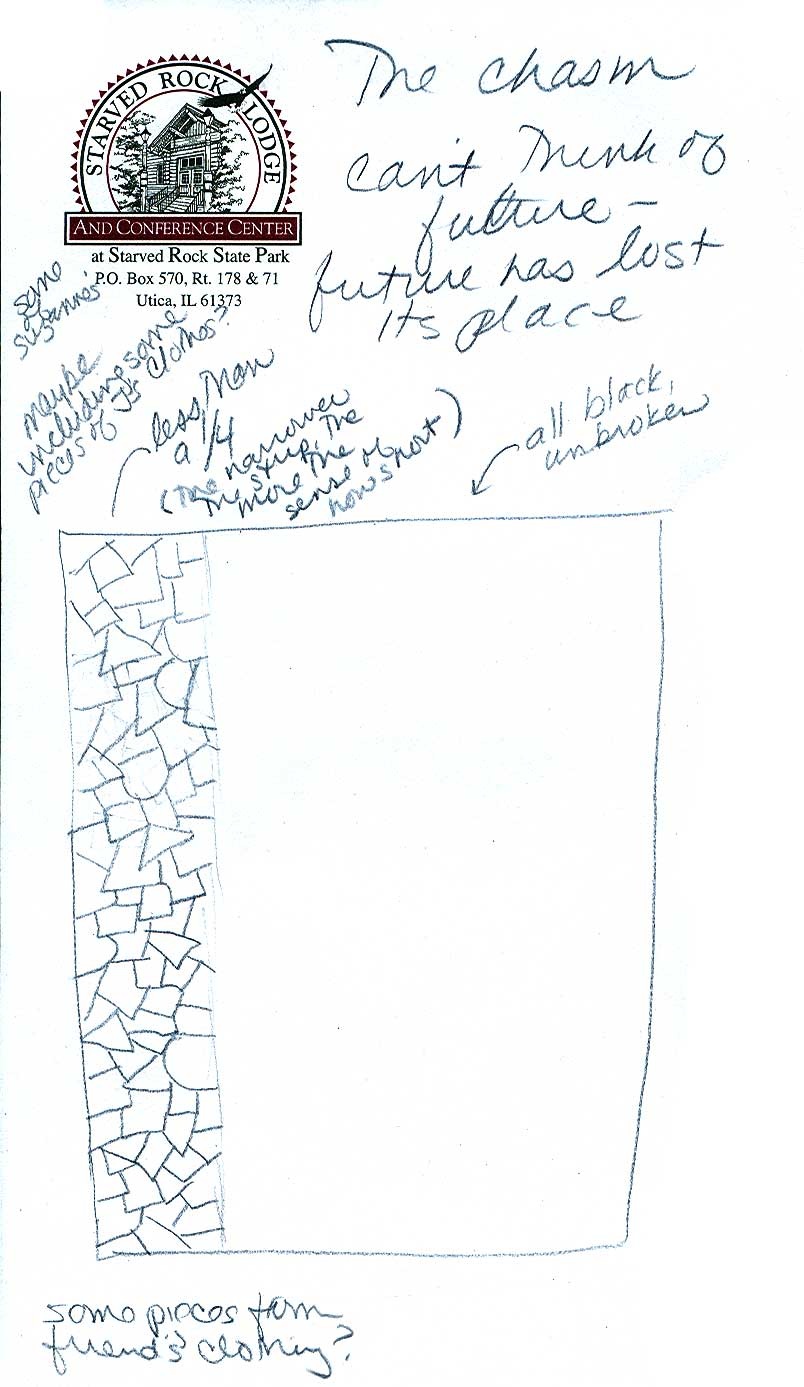

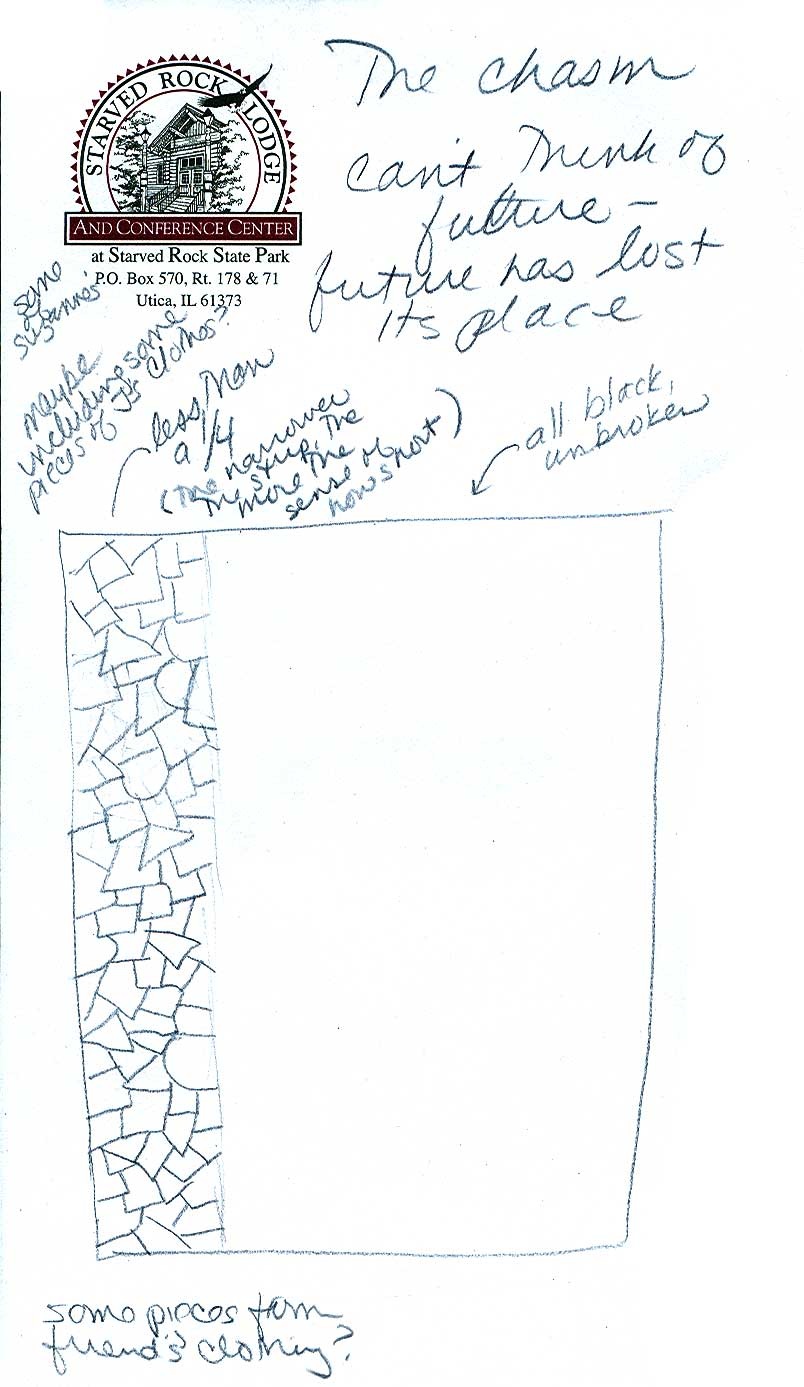

The weekend before the workshop, David and I went to Starved Rock State

Park. We had lots of time to talk, including sharing how bleak

the future seemed to both of us.

At one point in the weekend,

feeling the press of needing to come up with a third idea for the

workshop, I asked David for help. It immediately occurred to both

of us that our feeling of the future without Jeremy was something that

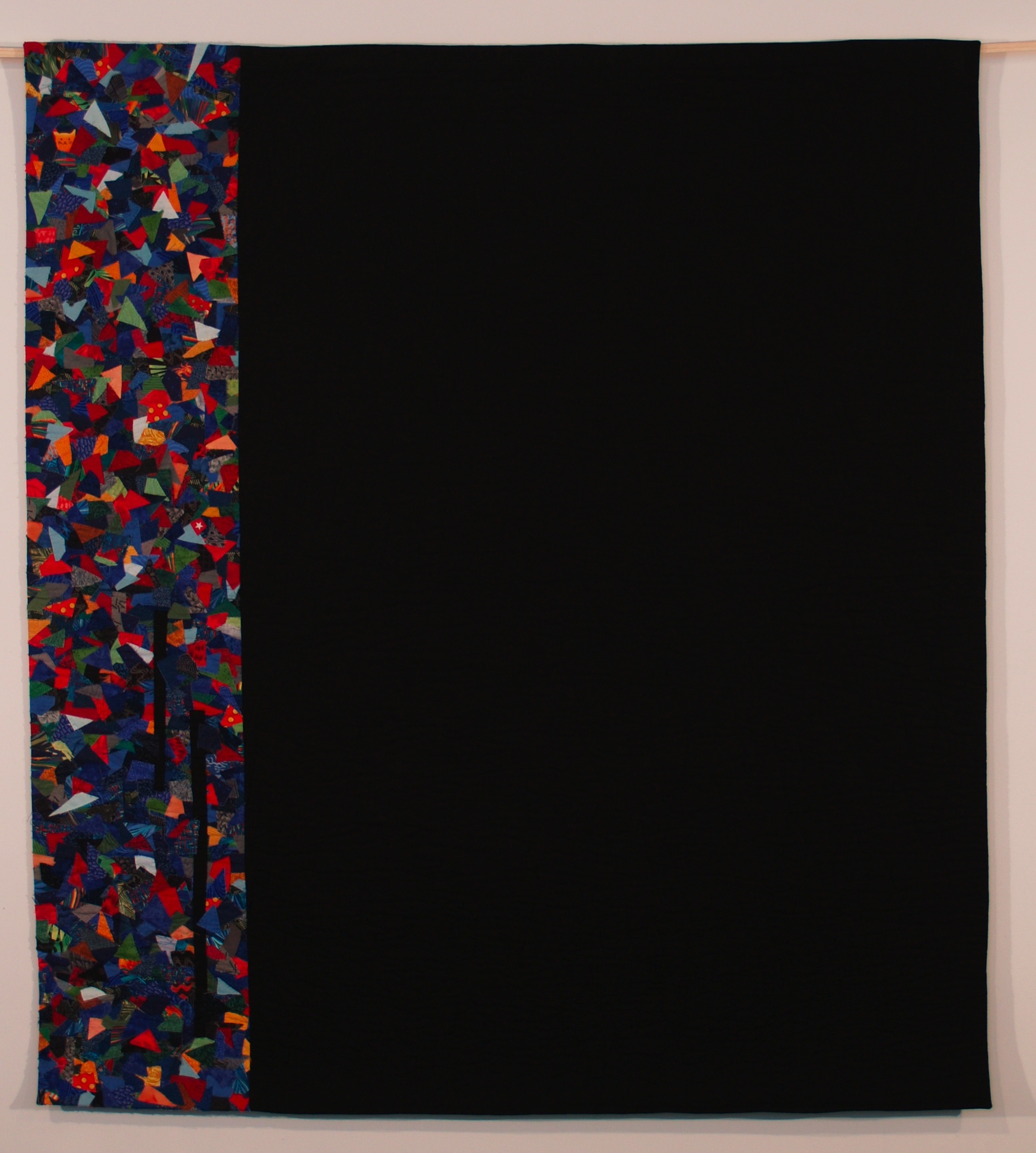

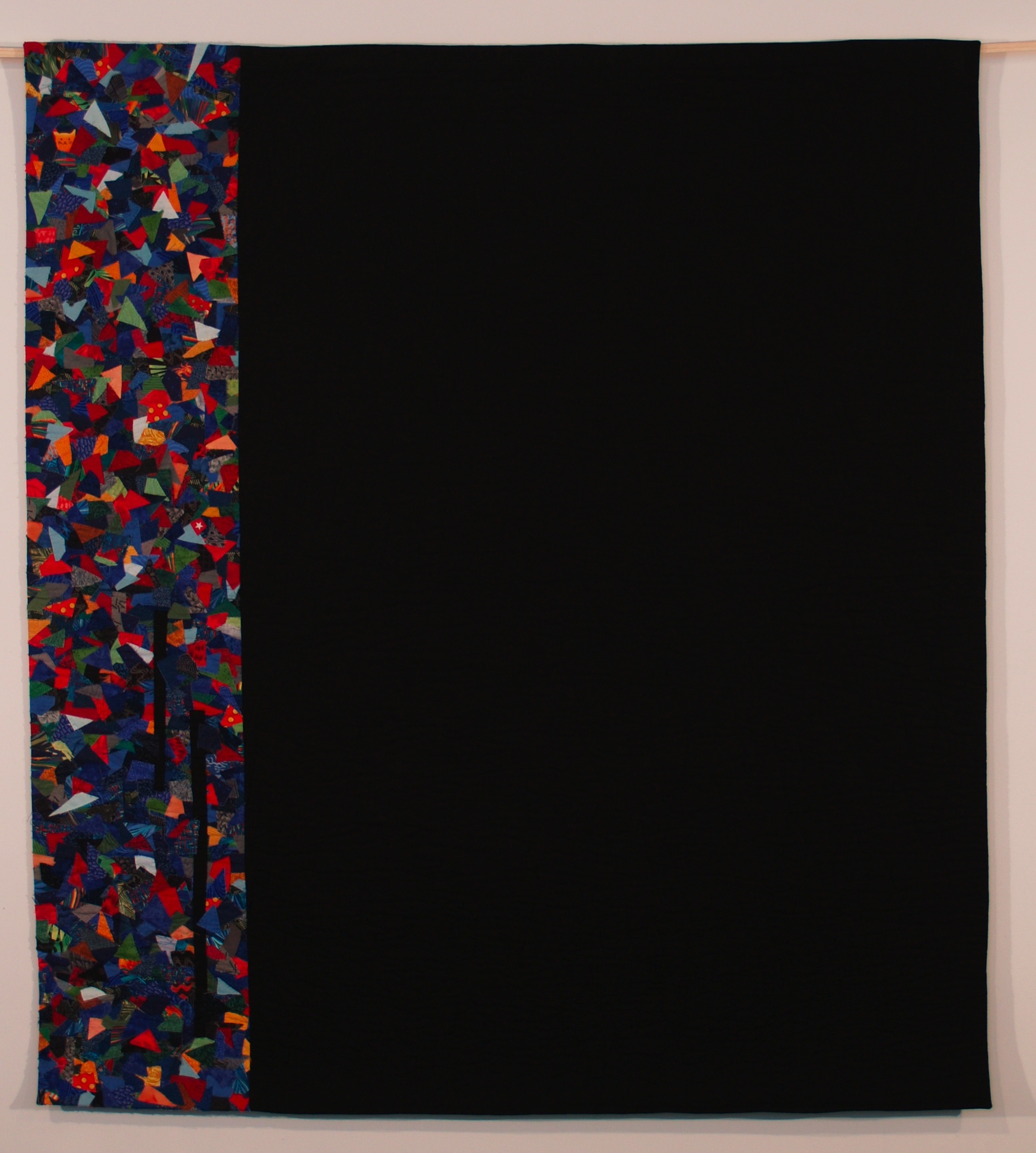

could be the central idea for a quilt. As we talked, thinking

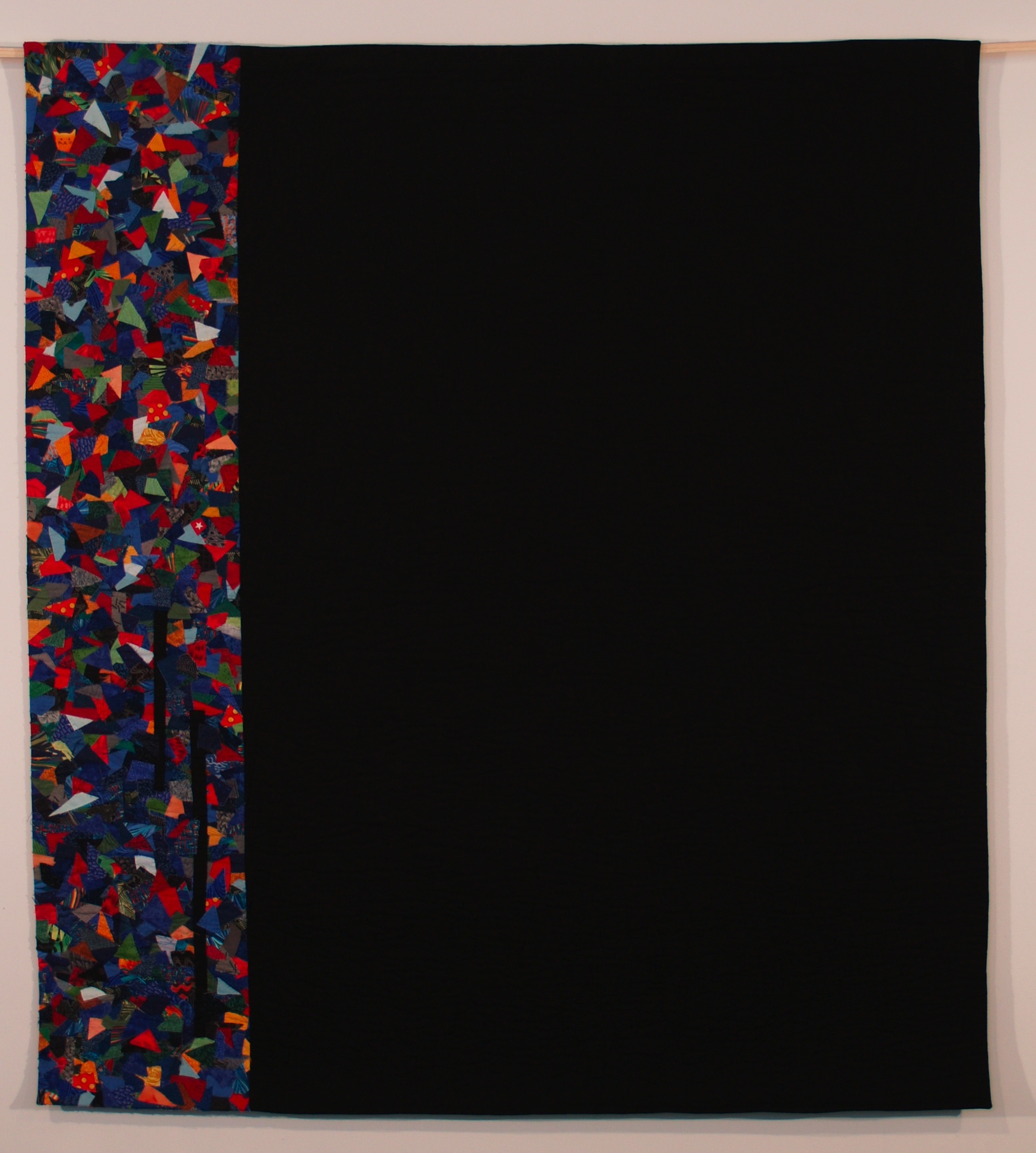

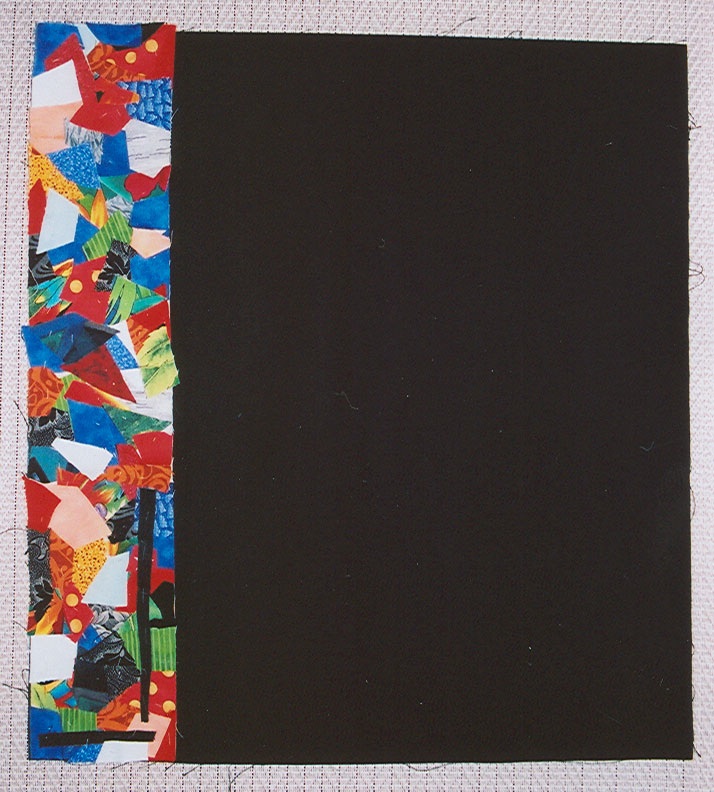

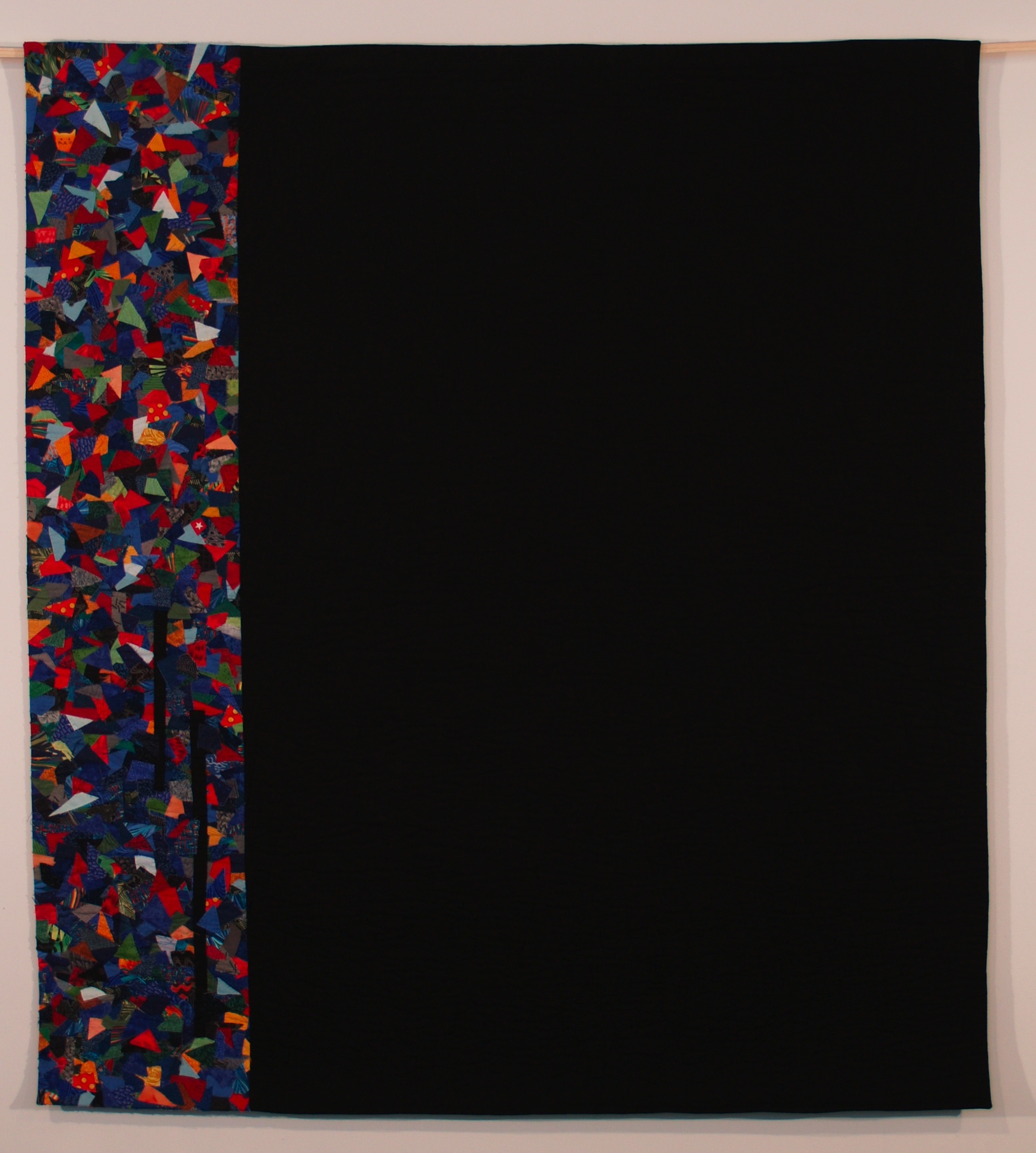

together of a possible design, I sketched out our ideas—a mosaic of colors on the left, which would

represent the brief span of Jeremy's life with us, and a chasm of

unbroken black on the right, representing our future without him.

So, I arrived at Design Camp with two ideas, high expectations, a good

deal of fear, and uncertainty about what direction I would be taking

with a quilt. What I didn't know was the extent to which this

workshop would be a transformative event in my life.

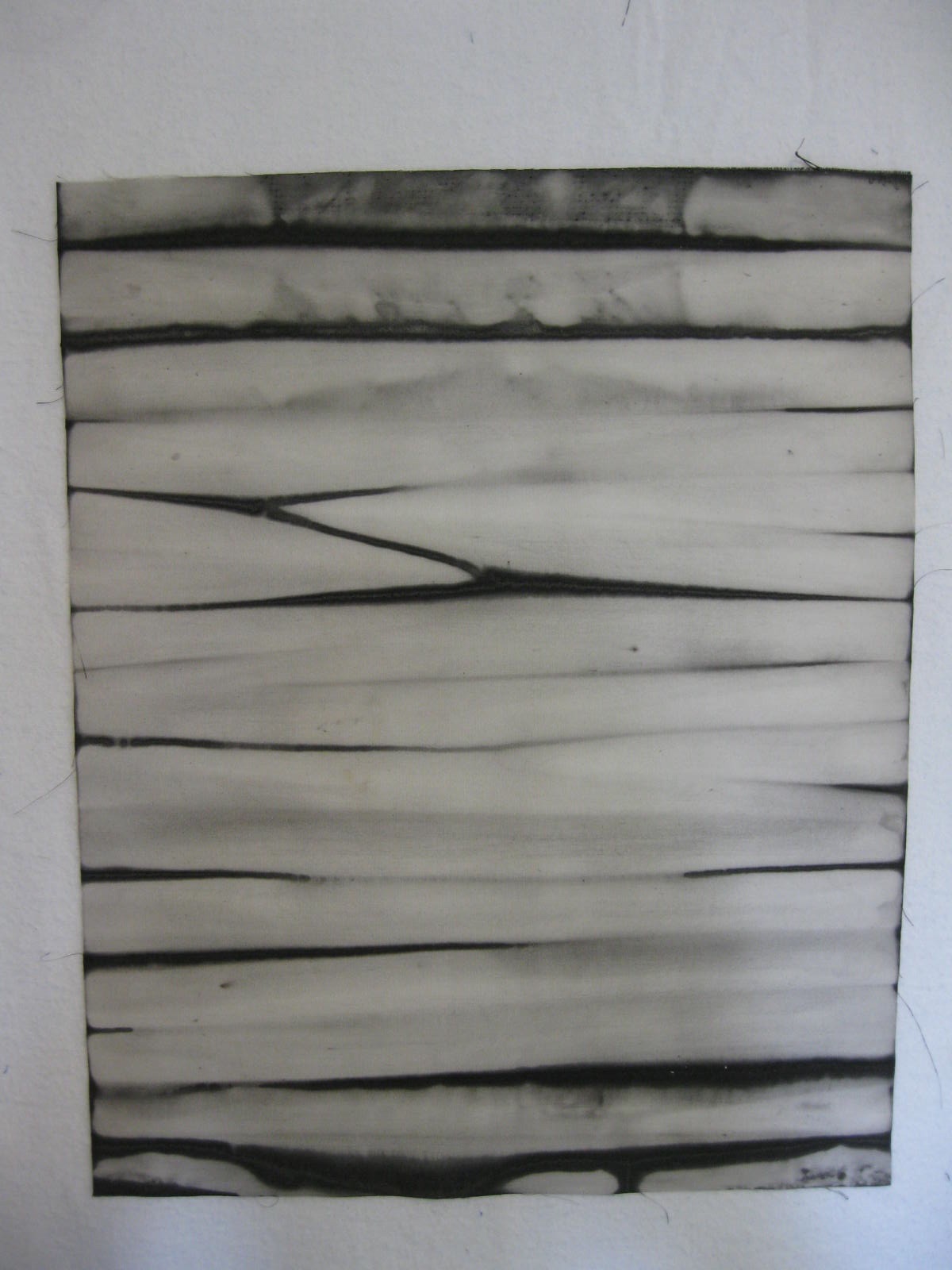

On the first day of the workshop, we were given an exercise: to

do a maquette (a small model) about a place that has been important to

us. I chose a quiet, peaceful place at the summer camp I went to

for years as a child--a pine grove, by the lake, away from the cabins

and activities, a place you could go to be by yourself.

I got to work, but all I could come up with was this (about 12"x15"):

I was disappointed—even disgusted. I wanted

to do something that was totally abstract, that conveyed the peace and

quiet of the place without reference to specific objects like the

trees, shore, and water. But I had no idea how to do it.

When Bill came by to see how things were going, I was so upset with the

inadequacy of what I had done that I could barely speak, and I sent him

away. Once I composed myself, he came around again, and got me to

talk about the place, about what it was I wanted to convey. He

then asked me, "What was the opposite of that place?" I answered

that it was the hustle and bustle of all the group activities of the

camp—lots of things going on with lots of people. "Make a

maquette of that," he said. So I did.

This one I was happy with. I felt that I had captured

in color and line some sense of what I was aiming for—the

liveliness of the usual camp day. "OK," said Bill, "Now go back

to the pine grove." And so I made this:

Yes, here it was, the feeling of the pine grove. Being able

to get to this abstract expression through the process of the exercise,

in one afternoon—this was amazing to me. I felt that

something was unlocked, that I could now do something I hadn't been

able to do before—or that I had reached into some well inside

myself that I hadn't known was there.

The next day, another exercise: to create a portrait, using color

in an abstract way to represent a particular person. Here it was,

an open door inviting me to work on a portrait of Jeremy, something

that could be the base for the multi-colored strip in the sketch David

and I had come up with.

This portrait (about 4x12") came to me spontaneously,

without a struggle. It put something of Jeremy's character, and

about how I felt about Jeremy, into a visual form. The choices of

colors and shapes came easily because I had in mind the central idea I

wanted to express: that this was about Jeremy, about his energy

and intensity, about his sharp edges, about the problems as well as the

joys. That his life was varied, but also limited.

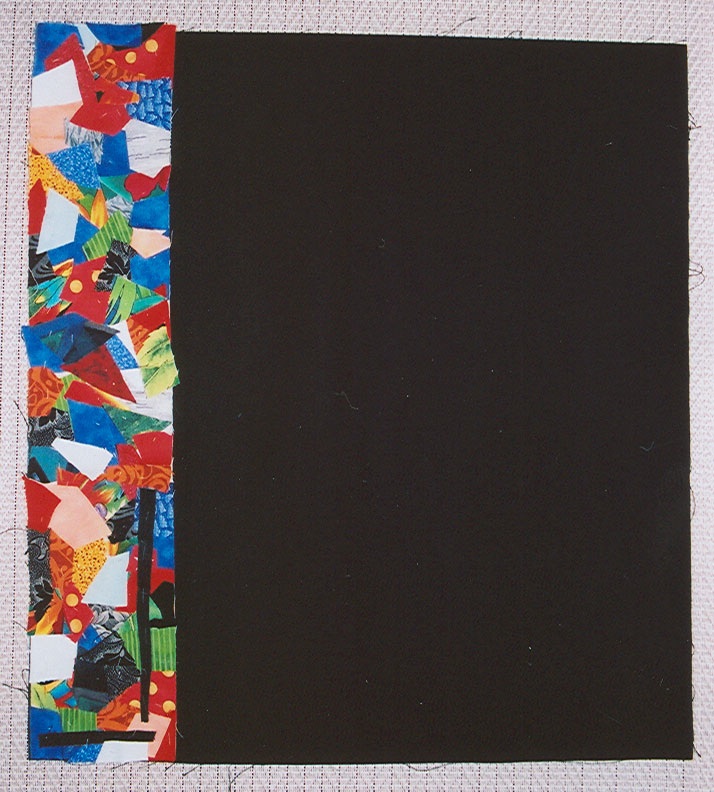

With the maquette of the mosaic side of the quilt already done, the

rest of the design came readily, putting the color of Jeremy's life

next to the blackness of our future. Here's a small maquette (15x16") of the full design:

But there were still many questions of size, scale and

method. For example, just on the issue of how to sew the small

colored pieces onto the strip: Definitely by hand rather than

machine, but should the edges be raw or turned under? If raw,

should I allow the edges to fray? How big should the pieces

be? How much should they overlap, if at all? In the past, I would have been frustrated by all these

decisions--frustrated that I didn't know the "right" answer, not

knowing what would look best, and that I didn't know how to figure it

out. But with this project, I felt entirely

different. I was content to just keep at it until I had a method

that felt right.

Here's the difference: In all the quilting I'd done previously,

I'd begun with a design made by someone else. For each of the

subsequent decisions: fabric, color and value, border, binding,

quilting—for each of these I had only the guidance of wanting to

make something that would look nice, perhaps even beautiful. But

now I had begun a quilt with an idea of my own, an idea about which I

cared deeply. For every decision I faced, I had this idea to

guide me. It wasn't a question of what "looked best," but of what

best conveyed the idea I wanted to express. This principle of

using a central, originating idea as a generative source for a work of

art of course applies elsewhere as well; writings by Twyla Tharp,

the choreographer, have been helpful to me (

The Creative Habit), as well as Roger Sessions

on musical composition (

Questions about Music). Here is the completed quilt, called

"Loss."

(51"x58")

In the process of making this quilt, my reasons for quilting changed

again. I still had pleasure in doing the handwork. And it

still helped me to live with grief. But designing and making this

quilt also brought out into the world the expression of something I

felt, something for which words were inadequate (despite months of

intensive journal writing).

Making this quilt was a private endeavor. It's not

something that will ever be used on a bed or hung on a

wall. It has served as a kind of therapy for me. And

it has also become art—something with the potential of

communicating to others, even if that was not my original

intention. When I was at the design workshop, well along in

working on the quilt design, I brought the small maquette over to Bill

to ask him a straightforward technical question. Oddly, he didn't

respond. When I asked again, he said, "Penny, it's not so easy

for me to look at this. I have my own losses too." It

hadn't occurred to me that something so personal, so specific to me and

to David, could also strike this kind of chord in another person.

As I worked on this quilt, I wondered if I would have any ideas for

further quilts. The next one developed somewhat by accident,

several months after Design Camp. I offered to Rick

Ortner's son Peter that I would make him a quilt for a college

graduation present. Instead of choosing one of the patterns I

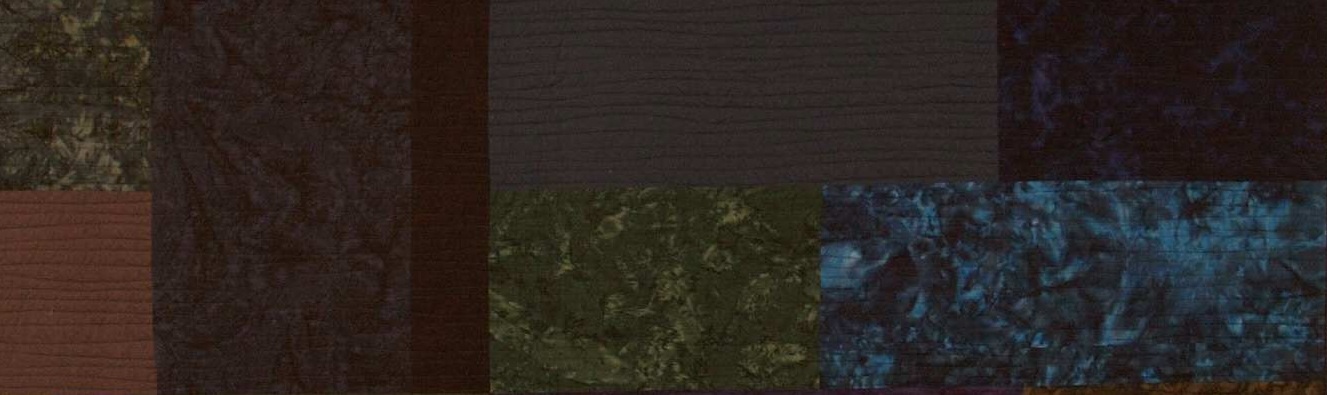

sent him, he asked, "How about something that feels aquatic or

subterranean, something dark with little gleams of light?" This

wasn't what I had had in mind, but I decided it would be an interesting

challenge to work with this as the central idea for a quilt, and I

collected fabric to bring to a second stint at Design Camp in

2006. As I got closer to working on the quilt, and considered how

much work would be involved in creating my own design, I thought it

might be a good idea to link up Peter's guiding notion with something

personal to me, something that might bring another level of meaning

into the quilt, and from which I would reap the personal benefit of

working through something that was disturbing me. As soon as this

occurred to me, I realized that I could link Peter's dark, subterranean

image with one of the images associated with Jeremy's death that I was

struggling with—the image of his body buried underground. I thought it possible that using this image for the

quilt, along with Peter's words, might serve to ease the grip of the

underground image for me. . . and it has.

(about 90 x 112")

And a detail that shows the quilting:

Here's the back of the quilt, which looks more

complicated, but was actually easier to do in terms of composition than

the larger pieces on the front.

Something more about the design process: My first maquette for

the quilt incorporated slivers of light-colored fabric to represent

stones (for me) and glimmers of light (for Peter). (In Jewish

practice, those who visit a grave place a small stone on the

gravestone, leaving behind a trace of their love and friendship.

I thought this personal meaning for me could work in line with

Peter's glimmers of light in the midst of darkness.) But when

I upped the scale for the quilt itself, the cloth slivers no longer

worked, and I

removed them from the design. In terms of Peter's idea, the

"glimmers of light" were still there, in the light portions of the

batik fabric. The idea of stones was set aside.

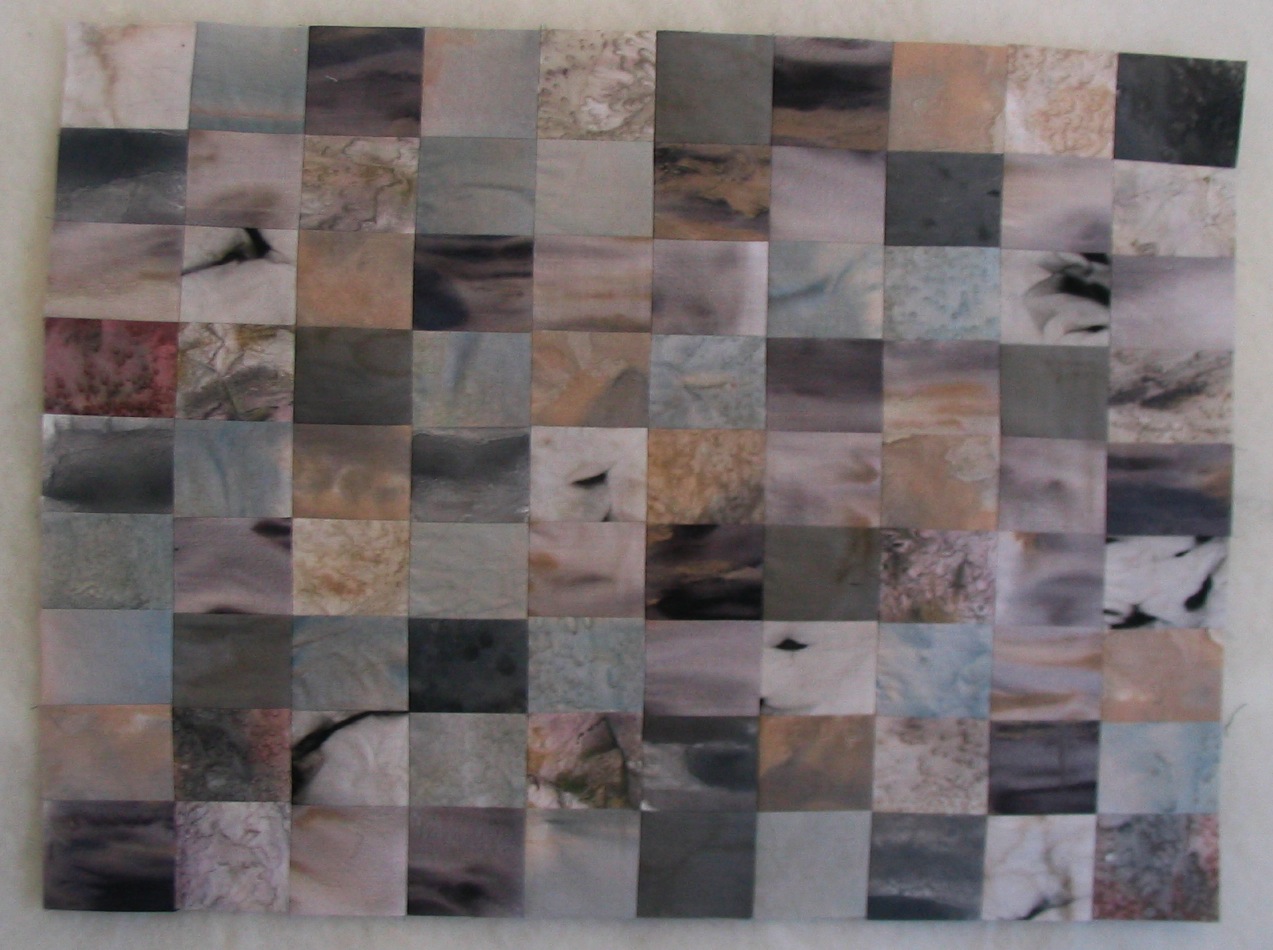

But I kept thinking about the stones. I tried several things

using commercial fabrics, either solids or fabric with stone-like patterns,

but none of them hit the mark. Here's one of those abandoned efforts (21x33").

The light gray section is the size of the headstone on Jeremy's grave,

and the dark gray band refers a layer of stones. I was not enough

moved by this to continue through to finishing it. It could be

that doing it either larger or smaller, rather than true-to-size, would

be better.

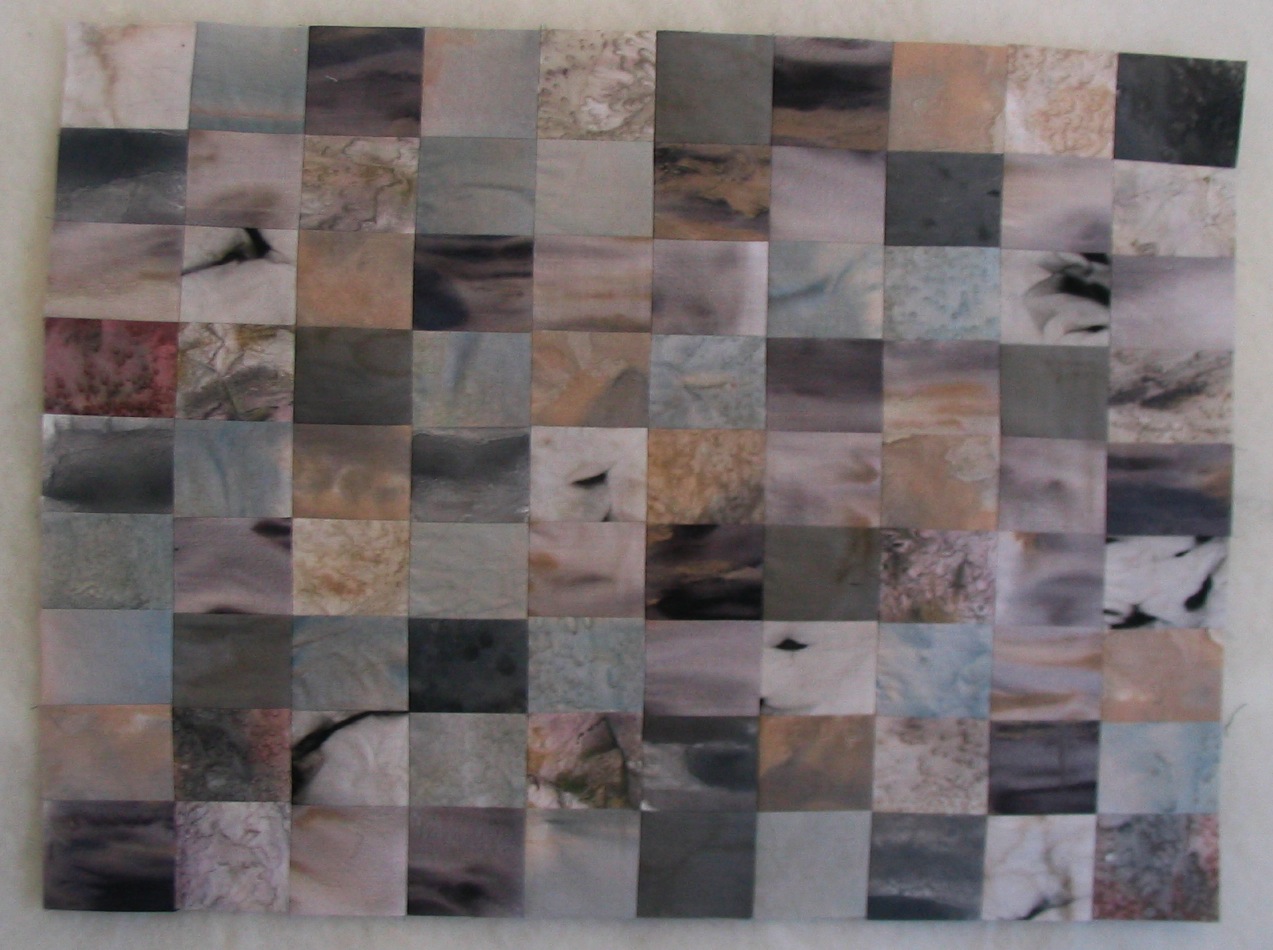

It became clear that commercial fabric was part of the problem, and I

decided to learn how to paint and dye my own fabric. I got the

confidence to try this by taking a summer workshop in watercolor and

pastel, in which I learned the principles of mixing color. I used watercolor to paint paper, which I

then cut up into stone-like shapes.

And

I used pastel to create a version of the Midwestern landscape I'd been

thinking about since Design camp.

(45 x 60")

I would like to make a cloth

version of this also, and am in the process of dyeing fabric to get the look I

want. The dyeing process is a significant challenge, but here's

why it's worth the trouble: a comparison of a commercial solid (on the right)

and a solid I dyed myself.

I've also painted and done monoprinting to make fabric that I could cut

up into stone-type shapes.

Some of this fabric has gone into small stone

portraits (each 4x4"):

I also took another

direction, putting aside the shape of stones and focusing instead on

color and texture .

(each about 11x14") |

|

When I was doing the quilting, the slanted

lines called to my mind rays of light in a forest, and I realized that

this quilt was related in color and feeling to the Pine Grove idea I

had put away from Design Camp.

I pulled out

the rest of the rectangles and did a more improvisational piece.

(about 67x70")

For the back of the quilt, I

wanted to use up more of the uncut leftover fabric, and to give a home

to some stone blocks that I had appliquéd and set aside.

I sliced up some of those blocks into

strips—I really like how this worked out.

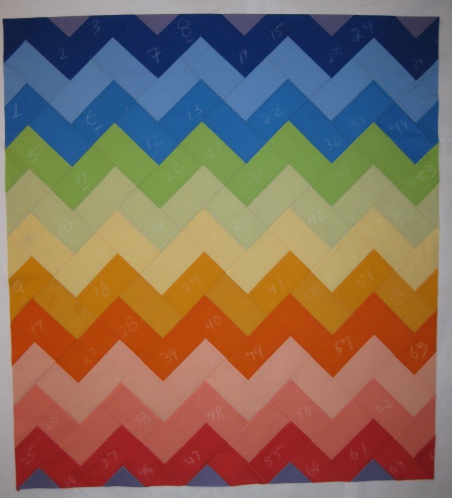

In the background of all this, since 2006 I've been planning and then

working on another major quilt. The quilt is not yet finished, but here is the top, in

progress. (Each tier of color is completed, but the four tiers are not yet sewn together.)

(about 60x64")

As I worked on the quilt

about Loss, I found myself thinking something like: "Without

Jeremy, the future for David and me is unremitting blackness, but I

don't want to think of Jeremy's future--his existence, of whatever

possible nature it might be--as this same blackness." If someone

asked me "Do you believe in life after death?" and asked for a yes or

no answer, the closest answer would be "no." And yet, when David

and I had to find words for the marker on Jeremy's grave, we chose this

epitaph, whose words are drawn from the Jewish funeral service:

May he find refuge forever

In the shelter of Your wings

And may his soul be bound up

In the bond of eternal life.

I couldn't say that I "believe" in these words, but I need their comfort.

The quilt in progress is about the metaphor of "the shelter of

your wings." When I first thought about this, a Durer watercolor

came to mind--the wing of a roller bird:

I thought

that Durer's colors might be a starting point also. The range of

blues from royal to aqua struck a chord, and the orange and black also

seemed good. In contrast to the straight lines used in "Loss," this

image demanded curves. For months I

sketched different combinations of curved lines and made many small

maquettes, using the four colors (and sometimes others) in various

combinations.

While the color black as used in the "Loss" quilt

signals emptiness and bleakness, here it carries a different meaning,

that of protection and warmth. It also calls up another image of

divine protection used in the Psalms: "in the shadow of Your

wings." Here are some details that show the construction process.

In the years that I worked on the plan for this quilt, I was interested

to see echos of my choices in other places. The curved

line as a sheltering image, which I took from the bend of a wing, is

also called up in the late medieval image of the Madonna of mercy,

something I remembered from my years as a medievalist:

|

Simone Martine, 1308-10

|

Piero Della Francesca, 1445

|

The color

combination I used in this quilt is also something I've noticed elsewhere.

When in China in 2007, I was struck by the standard

colors used in Ming architecture.

I've also been entranced by

Gina Franco's photographic images using orange and blue, some of which

have a similar color scheme of blue/aqua/orangey-red/and black:

When at the Art Institute earlier this

month, I noticed the same colors in some of Matisse's paintings:

Matisse, Dance

|

Matisse, Woman on a High Stool

|

And—totally

unplanned—my four books, two orange and two blue.

It's been five years now since I dismantled my study, but it has taken

me a long while to use the word "studio" for the room in which I work

on quilts. It's been easier to call it my "sewing room."

When I started a blog about my quilting in January of

2009, I called it "Studio Notes," partly as a way to accustom

myself to using the term. But if the room is a studio, then I am

claiming to be an artist. "When can a person legitimately call

themselves an artist?" Here is one artist's answer: "When you find

that making art is at the center of your life, then you can

legitimately call yourself an artist. Most artists make their

work because they are driven to make art; their level of dedication to

their life's work is very high and holds a sacred place in their

being." According to this definition, I qualify. The

central—even sacred--place that scholarship used to have in my

life is now occupied by art.

Two different paths have led to this life of art—one from

scholarship and one from craft. The clearest path would seem to

be from craft, as the making of quilts developed out of my making of

other things, and I began quilting as an extension of this craft

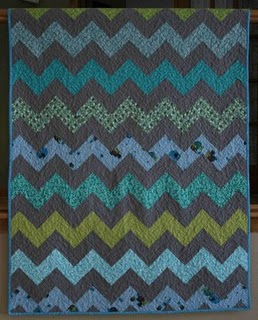

life. I still love making this kind of quilt, quilts in which I

begin with an already established pattern, which I then interpret with

my own choices, primarily of color.

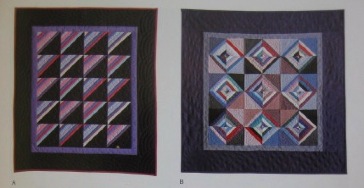

Here are some examples: First, from a traditional Amish

pattern of "Roman Stripes," I used the variation on the right

from Roberta Horton, An Amish Adventure, 2nd edition (C&T Publishing, 1996), p. 35.

to make this quilt for a young friend, Luke Matthew:

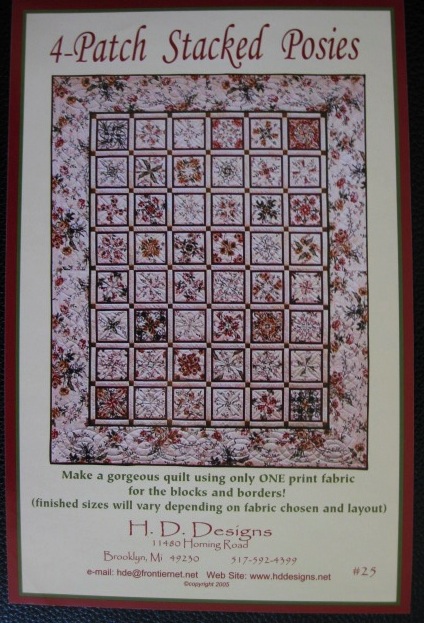

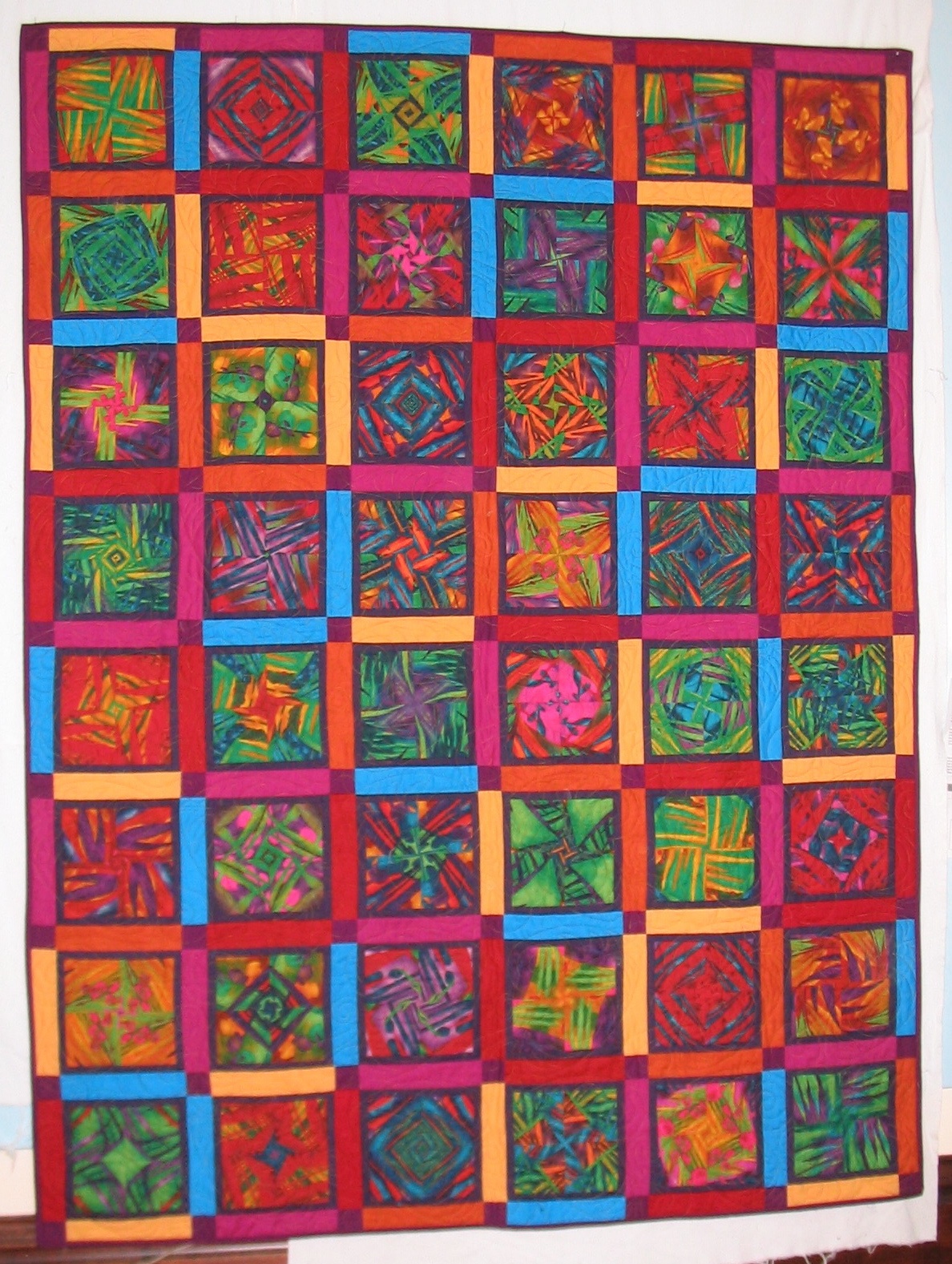

Here's a pattern for "Four-Patch Stacked Posie" and a few of the quilts I've made with the pattern:

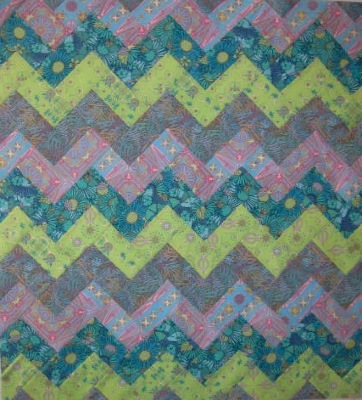

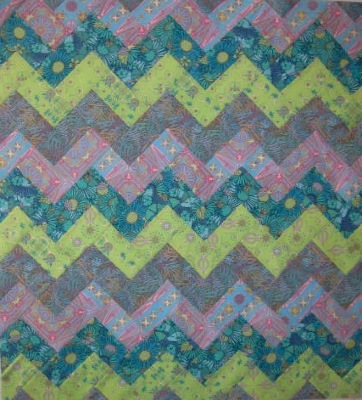

And here's a simple zig-zag pattern:

pattern by Amanda Jean of Crazy Mom Quilts |

my first version, fairly close in feel (about 32x40") |

and a second version done in solids

|

After trimming the edges of the last quilt, I had some pieced scraps

left over. Playing with those scraps, I came up with this piece (12x12"),

which I would put in the border between art and

craft. It was not done according to someone else's pattern, but

it was done without any underlying purpose or idea—just for the

fun of arranging shapes and color.

The quilts that function in my life as art, are those formed not from

someone else's pattern, and not for the main pleasure of manipulating

the materials, but those that come from a personal need—an idea

or emotion that is preoccupying me, that is disturbing me.

Although many artists work in response to the natural, physical world,

others work from the inside out. I am not responding to the

material world outside of me, but bringing out into material the world

inside me. Even the landscape pastel, done after taking many

photos of late winter farmland, was done without reference to the

photos, and ended up in the same palette that I chose for the Pine

Grove quilts—a palette that matches neither fields or forest, but

the feeling of quiet and stillness that I was seeking out as a respite

from my grief.

And

although it didn't occur to me until writing this talk, the very

different palette used for Loss is closely related to the colors I

chose for Shelter.

Although

different in intent, the quilts are bound together by the originating

motive of response to Jeremy's death.

This perhaps helps explain how I see my art as more closely connected

to my scholarship than to my years of knitting sweaters and

afghans. My scholarship also came from issues close to my heart,

issues that I was struggling with and wanted to resolve. The

issues were complex and difficult, and it took me years of work to

reach the understanding that I sought. The first book helped me

live as a woman amongst conflicting desires and demands, the second

book helped me live as a Jew. The quilts have helped me live as a

person who has lost a child. They have helped me live with grief

and guilt.

The feeling of inner drive is similar, and the scope and seriousness of

a book and one of these big quilt projects are also similar; they are

both work, not play. But the scholarship comes from a question

and ends with an answer. The quilts, on the other hand, come from

an emotion and end with expression. The life of the work once

it is complete is also very different. Much as the scholarship was

initiated and sustained from an inner drive, it was also intended for a

wide audience, and the writing and revisions were done with readers in

mind. The quilts are done for me. I have seen that others

respond to them too, and I am glad of that, but I am not making them

for an audience. I would never sell one of these quilts.

The extent to which this work is deeply self-centered is unsettling to

me, and a case can certainly be made that art should not be done as a

kind of therapy to work out one’s own problems—rather, the

purpose of art should extend outwards, to affect others. But for

me, the art has been therapy. It has enabled me to stumble, to

creep, back into life, to see further into the future than just the

next hour. It has provided me a way to live with grief. If

others are also moved by what I have created, that is good. If

the work helps someone understand the rupture and persistence of loss,

that's good. If it helps someone understand that for many people,

beneath the surface may be concerns or issues you cannot see, but

that are determining factors in that person's life, that's good

too. Though it was not my intent to communicate with others, the

fact is that my experience and feelings are not unique, and art that

embodies my experience can build a bridge to others. In this way,

perhaps I fulfill what Roger Sessions sees as the human responsibility

of the artist: "above all [the] awareness of the human condition,

a common involvement and a common stake in it" [Questions about Music (1970), 166].

There's more I could say about the processes of making scholarship,

making art, and the ways in which the habits/methods I've learned in

research and writing have also served me in the making of art.

Just briefly, here are some of the things I learned from doing

scholarship that have also helped me in making art:

-

the need for persistence, especially when you're ready to give up;

-

building a unified big-picture out of scattered fragments;

-

how to organize a work process, and how to get things done, even with limited time;

-

how to know when you're done, and how to know if the work is good;

-

the importance of talking with others about work

in progress—to share the work in a community, even while most of

the work is done in solitude.

And yet, despite the similarity of originating impulse/drive and in the

production of the work, the thing worked on is so different. The book, though it took much longer to

complete is so much smaller, and is so much more difficult to respond

to—you have to spend hours reading it, while the quilt can be taken in with one extended look.

When scholars run into each other, the standard question is "What are

you working on?" For many years I loved answering that question and the

exchange that would follow, catching up with friends and colleagues

about our scholarship. Now when I am asked that question by

another scholar, my answer can only be, "I've stopped doing

scholarship." This is another kind of loss for me—the loss

of the sense of belonging to a large, widespread community of

scholars. It also disrupted my job at Knox, and is part of the

reason I went to part-time status, eliminating the part of my work-time

that would have been devoted to research. On the other

hand, if an artist asks me the question, "What are you working on?"

then it is a question I can answer. I am grateful to have found

this path into art. I would give it up in an instant if I could

have Jeremy back. But he is gone, and art has helped me live

without him.

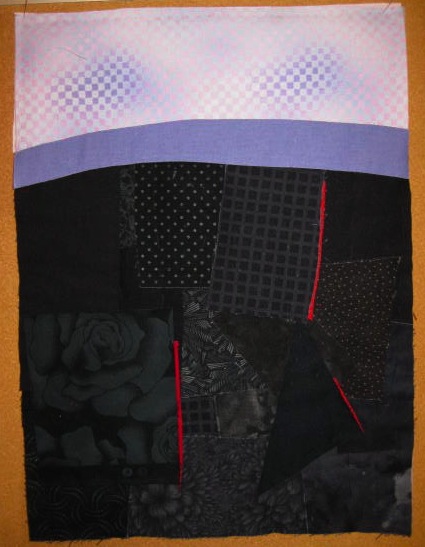

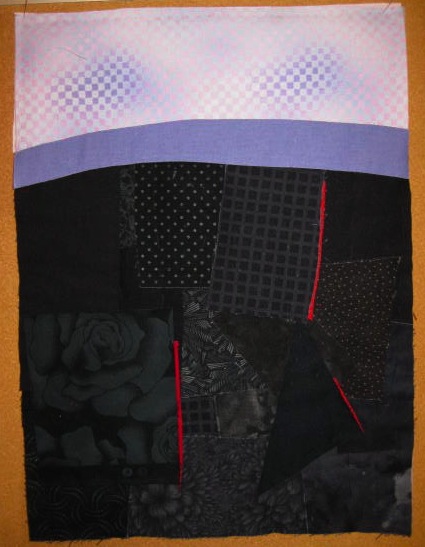

When people visit my studio they often ask me about the maquette pinned

to the upper right corner of the bulletin board.

|

(about 12x14") |

This maquette is for a quilt I was thinking of

several years ago, a self-portrait to be called "Beneath the

Surface." Not beneath the ground, as for Peter's quilt, but

beneath the surface of my everyday interactions with people. The

lavendar strip represents the calm appearance that I present to the

world, while underneath is the blackness of grief, lanced from time to

time by the anguish that pierces without warning. So many around

us hold beneath the surface some agony unknown to the rest of us.

As said by Philo of Alexandria, 2,000 years ago:

"Be kind, for everyone is fighting a great battle."

In closing, I would like to thank some of the many people who have

helped me along this new path. Thanks to the art faculty at Knox,

who have been exceptionally supportive from the time that I began

working on the Loss quilt--providing critiques of my work, allowing me

to sit in on classes, and just talking with me as though I were an

artist. Thank you Lynette, Tony, Mark, Claire and Rick for this

generous response to my work as serious and of consequence. The

support and critique of my quilting friends has also been crucial (with

special thanks to Mary Beth, Louise, and all the other Design Campers),

as has been the gifted teaching of Bill and Weeks. Finally,

thanks to David,

always and ever, my companion in love and in grief.

If you would like to look at a website created in memory of Jeremy, click here.

If you would like read more about my quilts in progress, you can follow my blog, "Studio Notes."

I was disappointed—even disgusted. I wanted

to do something that was totally abstract, that conveyed the peace and

quiet of the place without reference to specific objects like the

trees, shore, and water. But I had no idea how to do it.

When Bill came by to see how things were going, I was so upset with the

inadequacy of what I had done that I could barely speak, and I sent him

away. Once I composed myself, he came around again, and got me to

talk about the place, about what it was I wanted to convey. He

then asked me, "What was the opposite of that place?" I answered

that it was the hustle and bustle of all the group activities of the

camp—lots of things going on with lots of people. "Make a

maquette of that," he said. So I did.

I was disappointed—even disgusted. I wanted

to do something that was totally abstract, that conveyed the peace and

quiet of the place without reference to specific objects like the

trees, shore, and water. But I had no idea how to do it.

When Bill came by to see how things were going, I was so upset with the

inadequacy of what I had done that I could barely speak, and I sent him

away. Once I composed myself, he came around again, and got me to

talk about the place, about what it was I wanted to convey. He

then asked me, "What was the opposite of that place?" I answered

that it was the hustle and bustle of all the group activities of the

camp—lots of things going on with lots of people. "Make a

maquette of that," he said. So I did.

But there were still many questions of size, scale and

method. For example, just on the issue of how to sew the small

colored pieces onto the strip: Definitely by hand rather than

machine, but should the edges be raw or turned under? If raw,

should I allow the edges to fray? How big should the pieces

be? How much should they overlap, if at all? In the past, I would have been frustrated by all these

decisions--frustrated that I didn't know the "right" answer, not

knowing what would look best, and that I didn't know how to figure it

out. But with this project, I felt entirely

different. I was content to just keep at it until I had a method

that felt right.

But there were still many questions of size, scale and

method. For example, just on the issue of how to sew the small

colored pieces onto the strip: Definitely by hand rather than

machine, but should the edges be raw or turned under? If raw,

should I allow the edges to fray? How big should the pieces

be? How much should they overlap, if at all? In the past, I would have been frustrated by all these

decisions--frustrated that I didn't know the "right" answer, not

knowing what would look best, and that I didn't know how to figure it

out. But with this project, I felt entirely

different. I was content to just keep at it until I had a method

that felt right.