WHY QUILT? ONE PERSON'S STORY

A talk given to the Piecemakers Quilt Guild, Galesburg, Illinois

January 19, 2006

Why quilt? When I began quilting in the summer of 2001, I quilted

for reasons similar to those that had long propelled me to do other

kinds of needlework. But recently quilting has taken on a

different role in my life, and the type of quilting I'm doing has also

changed, most dramatically with the stimulus of a design workshop I

took this past summer. My talk will take you through this

development, with a sub-theme of how I learned to quilt--which I hope

may be helpful to those of you who are in the early stages of learning to quilt.

Although I'm relatively new to quilting, I have done needlework of one

sort or another for almost as long as I can remember, knitting a doll

blanket when I was about eight, sewing an apron on my mother's treadle

machine, and later adding embroidery, crochet, and needlepoint to the

continuing round of knitting and sewing projects. I learned all

of these from my mother. She was a great teacher, always patient,

encouraging me to do all aspects of the project myself, but also

willing to finish up something that was too hard for me or that I'd

lost interest in, or just to spare me a tedious part. She taught

me how to correct mistakes, and also when it was the better part of

valor to leave a mistake in: "It shows it's hand-made!" she

would say--an attitude that has protected me from perfectionism in many

aspects of my life.

Knitting is the main needlework I've done throughout my life.

Why have I knit all these years? The reasons have to do with both

process and result. I enjoy the feel of knitting--the repetitive

hand motion, the contact with beautiful yarn, the satisfaction of

seeing a garment or afghan grow beneath my hands. And the

knitting is a soothing companion in situations that don't need my full

attention or are boring (watching TV, waiting in a doctor's office), or

in situations that may be stressful (some committee and faculty meetings).

Most of what I knit is done in a very simple stitch so that I

don't have to look at the work, keeping my active attention to what

else is going on. Like my mother, I carry around my knitting,

ready for opportunities to knit a few more rows. The results of

the knitting are gratifying too, providing hand-made presents for many

people in my life. I rarely knit for myself. For me, a big

part of the pleasure of knitting is having something on hand to give to

others. The same motivations go into much of the needlepoint,

embroidery, crocheting, and sewing I've done over the years.

For most of my life, I never gave any thought to learning to quilt.

It was not something my mother did, and learning from her was how

I learned needlework. I didn't have any friends who quilted

either. But in the spring of 2001, quilting came to my attention

in two ways. A group of Knox students made a raffle quilt

together. I was moved by these young women working together on

the quilt, doing a traditional craft to benefit a contemporary cause.

Not long after I saw their quilt, I got a letter from a young

friend, a colleague's daughter, whom I had previously taught to knit and

sew. She was going to be home from boarding school for the

summer, and she wrote asking if there was a project we could work on

together again, maybe some more knitting, or perhaps we could do some

quilting? With the appealing prospect of having Katie as a

companion, I took on the task of learning to quilt.

Since I knew no one who quilted, I learned from books. I went to

the public library, pored over the books in the quilting section,

brought home a pile, and started sewing. Katie and I started out

with a variety of simple, pieced 12" blocks, she for a tote bag and me

for placemats, and we were off. We also searched for a project

that we could both easily work on once she was back at school, and

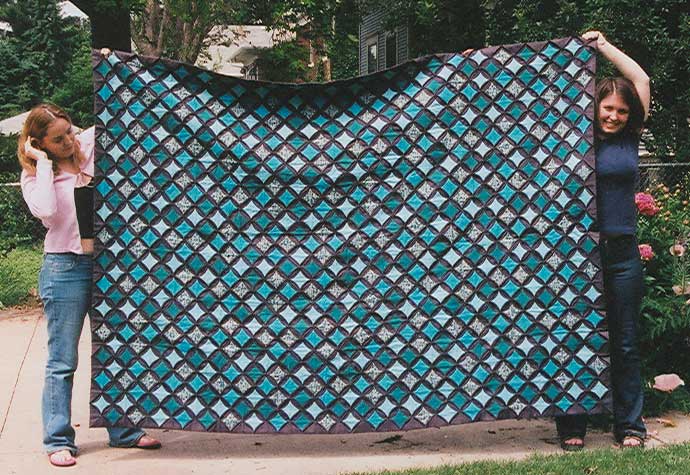

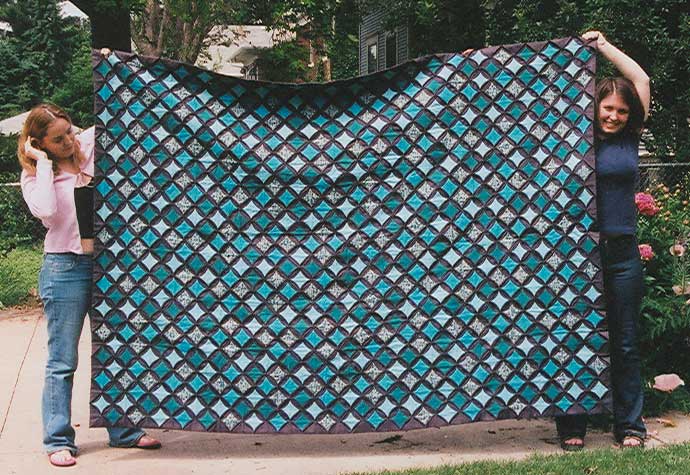

decided on a cathedral window quilt. (Held up below by Knox

students and quilting friends, Claire Rasmussen and Claire Leeds.)

I did the dark gray foundation pieces on my machine, and then sent half

off to Katie for the hand sewing of the colored inserts. It was a

great project to share, and it took us about eighteen months to finish.

We didn't use the traditional white background for this pattern,

as I imagined the quilt getting dragged around dorm rooms for some

years to come, and we didn't use scraps for the inserts, because I as

yet didn't have a stash of fabrics to take scraps from.

At the same time that I worked on that quilt, I made many, many machine-pieced potholders. Here are the first ones I made.

Not a very good use of value in the green ones, but I was learning! I found this to

be a good way to try out different block patterns, different color

combinations, value contrast, and techniques, and I loved having little

quilted gifts to give people, something that would take me just a few

hours from start to finish. Making potholders fulfilled some of

the same purposes that my earlier knitting and sewing had--enjoying the

process of making, and having something to give away as a result.

Here are a few more:

But I also wanted to find something that was portable, some handwork

that I could carry around with me. Hand-quilted placemats were

just the ticket. I would machine piece the block and border, but

then do the quilting by hand. The small size of the placemats

were perfect for a traveling project, and the different designs and

plain borders gave me a field for learning hand-quilting. After a

set for myself, I moved on to a set for my sister, trying some more

complicated piecing and experimenting with pieced borders.

Then I did another two that were appliqué.

I've also done some wall-hangings, mostly from class projects, again

small enough that I can carry them around with me to do handwork,

whether hand-quilting or needle-turn applique.

So, as I learned to quilt, I found that it fulfilled the same needs

that knitting and other needlework projects had in the past--enjoying

the process and having hand-made things to give away. But there

were also additional pleasures, and some additional frustrations.

The first added pleasure was that quilting was something I could

do with other people. Knitting, in contrast, was almost always a

solo endeavor, other than when I asked my mother for help, and I did

one baby afghan for which my mother, in the last months of her

life--in Galesburg at in a nursing home--did the fancy edging.

In contrast to the one-person nature of most knitting, I enjoyed the

collaboration possible in quilting--not the group hand-quilting around

a frame (not something I've done), but the joint planning and execution

of a project: the cathedral window quilt with Katie, a sampler quilt I

have in progress with a second young friend, a sampler quilt done with

Knox alumni, and another sampler quilt done by the feminist student

group at Knox, to which I contributed a block. And after having

found my way to the Guild a few years ago, the camaraderie of our

meetings, and that of classes, whether sponsored by the Guild or

elsewhere, have added further pleasure.

The other main added pleasure was the huge variety of beautiful

material available--many more choices possible than the run of yarn for

a particular sweater project. But this pleasure was also one of

the frustrations: How was I to choose from among all these

fabrics? And from all the possible patterns? The choices in

the other crafts I'd done were much simpler. For knitting, for

example, I'd choose a pattern from a somewhat limited range of

possibilities, choose the color I liked best from the limited range of

yarns available to me in the appropriate gauge, follow the directions,

and complete the project: a very limited set of choices compared

to what we face when contemplating a quilt. All the more reason

why I stuck to small quilting projects for a long time--I could

experiment with different choices and see the results quickly, without

committing major resources of time and energy. And while my

ability to use color, value, and shape improved through these small

projects, I was very much aware of how much it might help me to learn

more about design, especially about color. I read a few books on

color, worked through a textbook on graphic design, and gleaned what I

could from various classes and workshops. While most quilting

classes focus on a specific techniaue, some teachers include discussion

of design. I was especially helped by a small class Suzanne

Marshall did for a few of us in her home in June of 2004--talking to us

about the development of a quilt from the first idea all the way

through to decisions about borders and binding.

With some increased confidence, I undertook a bed-sized quilt early in

2004--a quilt for my son to take with him to college. We chose a

log cabin design, in his favorite color, blue. Even with the

restricted color palette, I had a lot to learn. I picked out a

range of muted blues that were appealing to me and did up a block.

I showed Jeremy the sample block--the one in the upper right

corner below--and asked him if this was OK. "But Mom," he said,

"I asked for blue."

Right--I could now see that the muted colors I'd chosen read as grey.

I went out and bought a bunch of brighter blues, but I didn't want

to waste the more muted shades that I'd already bought, so I mixed the

two together, something I would never have done had it not been for the

mistake of the first purchase. As it turns out, I think the color

work in the quilt is much more interesting with the combination of

muted and bright than it would have been with either alone.

I don't usually do projects to a deadline--I just work on something I

want to be making, and give it whenever it's done. But Jeremy was

to begin college in the fall of 2004, and I wanted the quilt finished

by then. I had almost all the blocks done by the beginning of the

summer.

And then Jeremy died.

For a week or so, the dark chasm that loomed on all sides was kept at

bay by the round-the-clock presence of family and friends. But

then one has to step back into the routine of life, and I found this

very difficult. Because it was summer and I wasn't teaching, my

days were unstructured by work. The scholarly research I had

planned to do was of no interest to me. Reading--fiction or

anything else--which had always been such a large part of my life, was

also of no interest. One day it occurred to me that sewing might

help me pass the time--the days seemed so long. I went over to

the corner where I kept various projects, and found some small

appliqué blocks that I had forgotten about, all set to be sewn.

It turned out this was just what I needed to help me thorugh the

day. Very simple shapes, one color against another in a fairly

restful palette, the repetitive calming motion of the hand-sewing, and

the satisfaction of one block after another completed, each taking as

little as a half-hour.

These blocks were quickly done, but my need for this simple kind of

sewing wasn't. The sewing was a kind of analgesic, almost an

anesthetic, keeping at bay the images of Jeremy's accident, the images

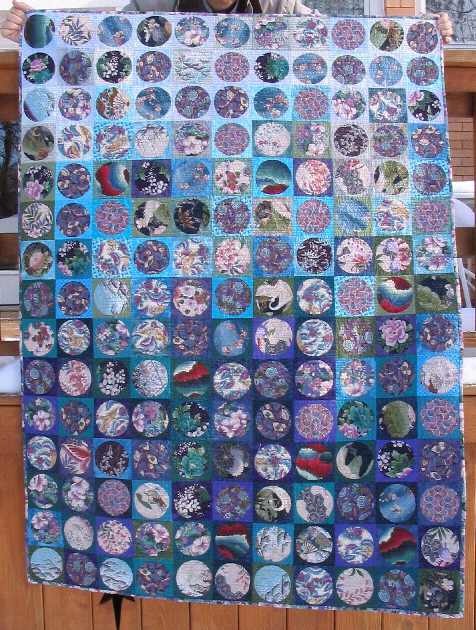

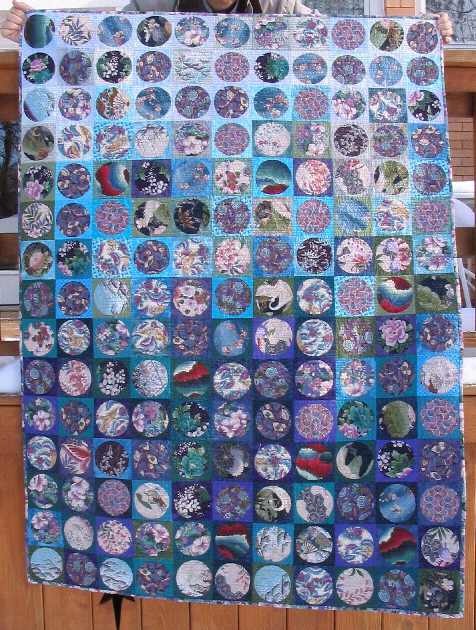

of him dead. I lined up another project, this time going even

further into the hypnotic effect of repetition by sewing again and

again just one simple shape, a circle. For the circles, I used a

variety of oriental-style prints, and for the background a variety of

shades, working out from the teal, turquoise, and green I'd used in the

cathedral window quilt. I didn't have a final product in mind.

I just kept matching up a circle with a piece of background that

made an appealing match and sewed. If I had ended up with a

couple of placemats, that would have been fine. As it turned out,

by the time I no longer felt I had to keep sewing circles, I had enough

for a large wall-hanging.

So, back to the question of "Why quilt?" Why I was quilting had

changed--it had become necessary to me in a way no needlework had ever

been before. Not just a pleasurable pasttime, with the nice

result of having gifts to give, but something I needed to do for my

sanity, that I needed to do to get through each day. And the

resulting quilts? These were no longer something I could give

away. I needed them by me, as a reminder and continuation of the

process of mourning.

As I worked on the simple appliqué pieces, I also considered

what to do about the log cabin quilt I had been making for Jeremy.

How could I finish it, now that he was no longer here to receive

it? But how could I discard this work I had been making for him?

I finally thought of a way that I could finish the quilt, but

embed in it my grief over his death as well as my love of his life.

When Jeremy died, I had only three blocks left to complete the

forty-eight that would make up the top. I decided to change the

design for the last three blocks, making them off of a five-sided

center, rather than off the four sides of a square; when set into the

barn-raising pattern Jeremy had chosen, it expressed for me the way in

which his life had so abruptly gone off course. I thought a lot

about where to put the three last blocks. I put them together

rather than scattered through the quilt; towards the edge rather than

in the center; towards the bottom rather than the top; catching one's

vision, but not dominant.

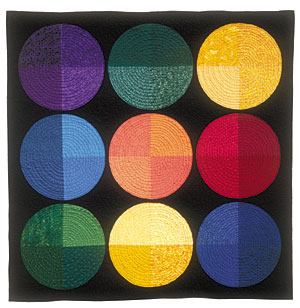

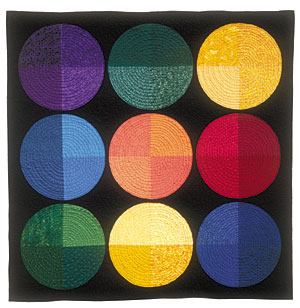

In the midst of working on these quilts, in the winter of 2005, a

magazine article on contemporary abstract quilts caught my eye.

These quilts by Bill Kerr and Weeks Ringle reminded

me of a combination of Amish quilts, which I like very much, and modern

abstract art. Here are a couple of examples of their work; (their

company is called FunQuilts):

|

|

| Jewel Box, by FunQuilts |

Iced Coffee, by FunQuilts |

I went to the quilters' website to look further, and noticed that they

were offering a week-long design workshop in the summer, just up in Oak

Park. The point of the workshop was not to teach how to make

quilts like theirs, but to teach a design process that would enable

students to make the quilts they wanted to make, utilizing a design

process that would be the central focus of the workshop. Color

work would be a key topic in the workshop--indeed, Bill and Weeks had

published a book on the subject. It sounded like a week in this

workshop would help me accomplish what I'd had trouble getting on my own

from reading and making those dozens of potholders, so I signed up.

To prepare for the workshop, we were asked to bring with us a few ideas

that might serve as inspiration for a quilt. The examples they

gave were:

- memories of three significant events in your life, or

- three things (big or small) that you'd like to do in your lifetime

Neither of these suggestions worked for me. In terms of

"significant events," Jeremy's event pushed aside all others, and I

felt that I was already doing the quilting I needed to do to help me

cope with his death (the folk art appliqué, the circles, the log

cabin--with the latter two still in progress at the time). And

things I'd like to do in my lifetime? Without Jeremy, the future

was a void--my life was behind me, and I had no thoughts of doing

anything further, large or small.

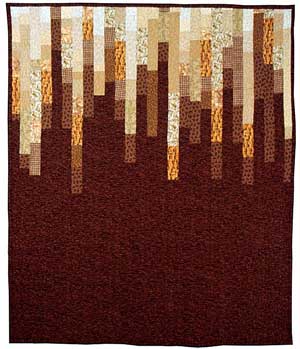

So I let my thoughts drift to other things that might be a central idea

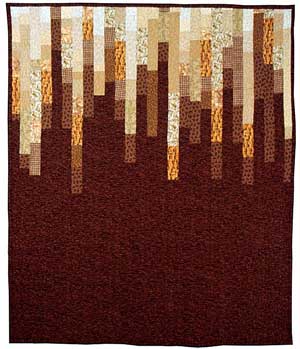

for a quilt, and decided on the midwestern landscape. The colors

of the fields in late March were dusky shades of brown and green, with

an overcast sky of a bluish gray--very appealing to me. A transported New Englander, I have

come to love the midwestern landscape,

and the soft, muted colors of late winter and the gentle rolling lines

of the farmland were something I thought I'd enjoy trying to capture in

a quilt. I went out and took photos, I kept an eye out for quilts

using concepts or techniques that seemed appropriate, and browsed

through artists whose landscape work I thought might be helpful. I

bought a sketch book--an entirely new thing for me--and made lots of

pencil sketches of what I might do. And I bought fabric,

venturing into hand-dyed fabric, which I hadn't used before, but which

seemed right for what I had in mind. I enjoyed the process of

letting the idea roll around in my mind, gathering up further ideas and

materials in the months before the workshop.

But then it was June, Design Camp was a week away, and I realized I was

bringing with me only one idea, not the three they had asked for.

I rummaged around in my head, but didn't find anything else.

I half-heartedly thought of one more idea and did a sketch or

two. The weekend before the workshop, my husband David and I went

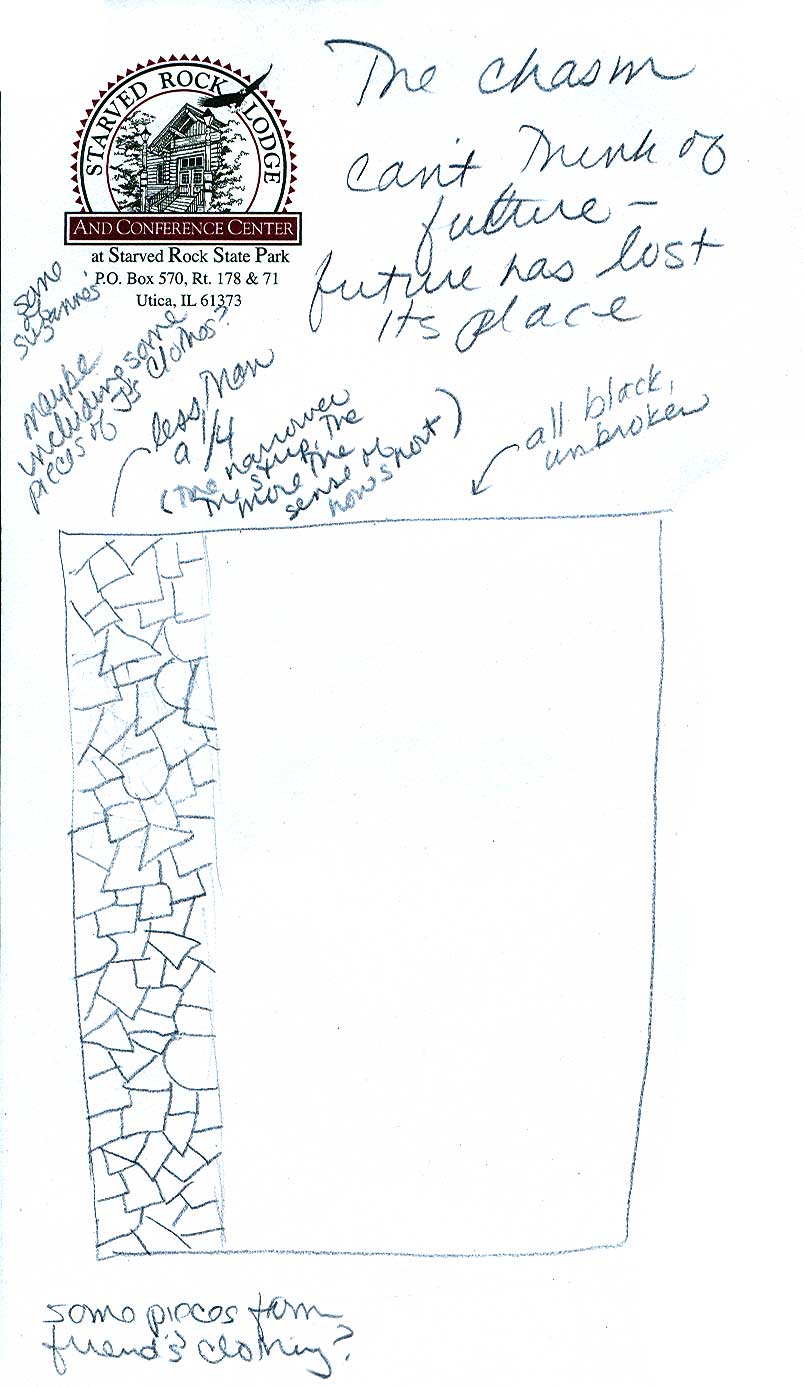

to Starved Rock State Park, a rare quiet time away just the two of us.

We had lots of time to talk, including sharing how bleak the

furture seemed to both of us. At one point in the wekend, feeling

the press of needing to come up with a third idea for the workshop, I

asked David for help. "Any ideas?" It immediately occurred

to both of us that the feeling of the future without Jeremy--this was

something that could--even should--be the central idea for a quilt.

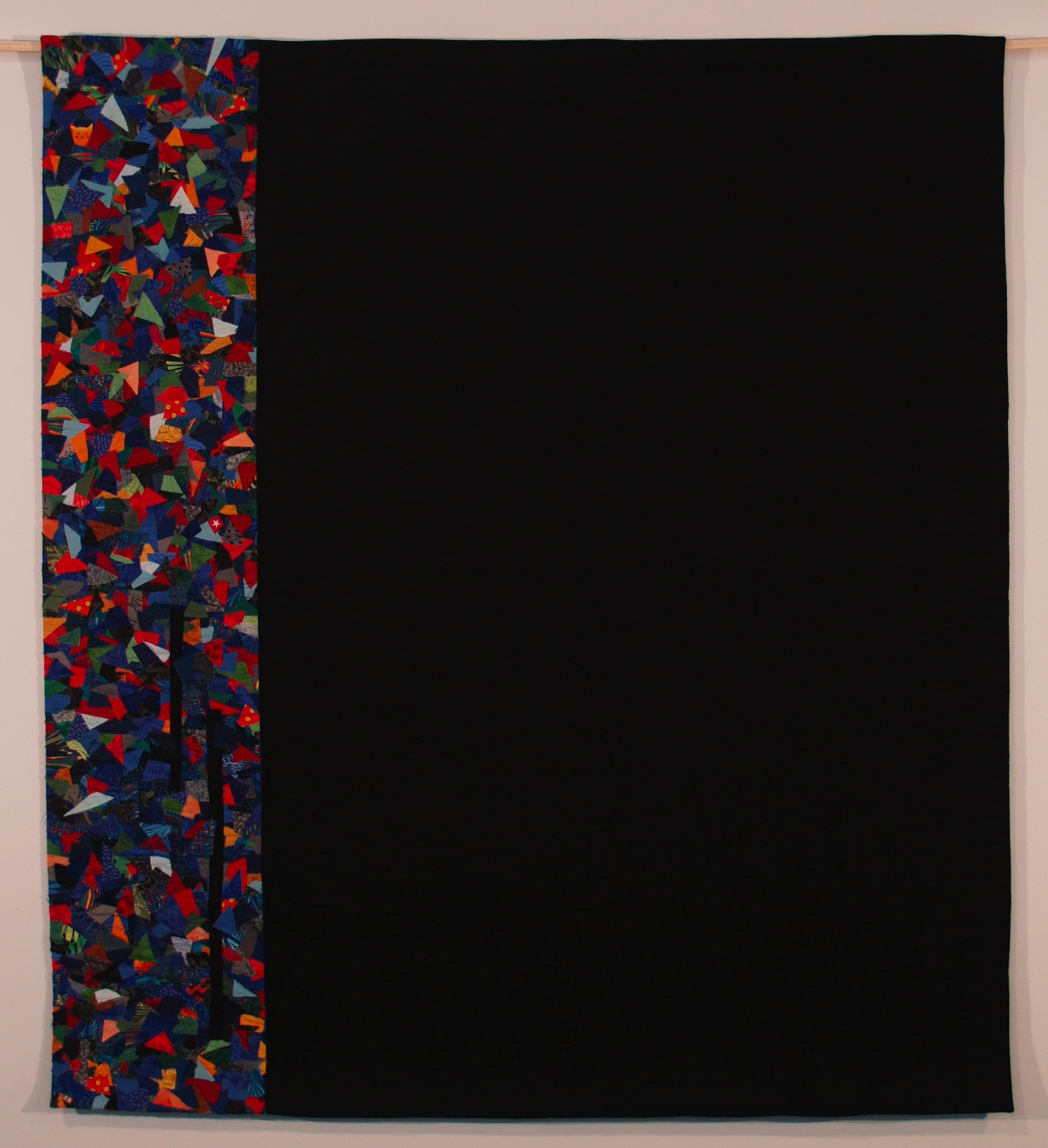

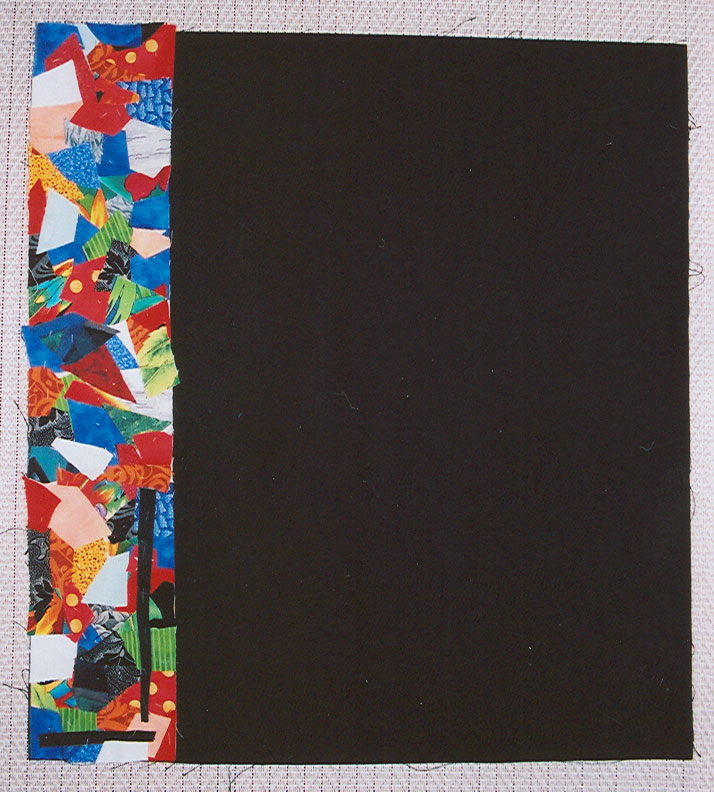

As we talked, thinking together of a possible design, I sketched

out our ideas--a mosaic of colors on the left, which would represent

the brief span of Jeremy's life with us, and a chasm of unroken black

on the right, representing our future without him.

I arrived at Design Camp with high expectations, large fears, and great

uncertainty about what direction I would be taking with a quilt.

Would I learn what I was hoping to learn? Would I be able

to work from an idea of my own to a quilt design? Which quilt

would I end up working on? With the stimulus and inspiration of

great teaching by Bill and Weeks and the tremendously supportive

encouragement of the other students, the workshop surpassed all I

had hoped for; it was a transformative event for me. What I want

to do for this last portion of my talk is give you a sense of what the

workshop was like, and how it changed why I quilt.

On the first day of the workshop, after a presentation and discussion

of some principles of design, we were given an exercise: To do a

maquette about some place that has been important to us. (A

maquette is a small model, done in cloth. You take a small piece

of batting, perhaps 15" square, and then cut up pieces of fabric and

lay them down on the batt, making a kind of sketch in fabric. We

had lots of fabric to choose from--not only what we had each brought

with us, but many bins of scraps from the teachers' studio.) The

idea was to work quickly but thoughtfully--we had a couple of hours to

spend on this. The place I picked to portray was a pine grove--a

very quiet, peaceful place at the summer camp I went to for years as a

child, a place by the lake, away from the cabins and activities, a

place you could go to, just to be by yourself.

I got to work, but all I could come up with was this.

I was disappointed--even disgusted. I wanted to do something that

was totally abstract, that conveyed the peace and quiet of the place

without reference to specific objects like the trees, shore, and water.

But I had no idea how to do it. When Bill came by to see

how things were going, I was so upset with the inadequacy of what I had

done that I could barely speak, and I sent him away. Once I

composed myself, he came around again, and got me to talk about

the place, about what it was I wanted to convey. He then asked

me, "What was the opposite of that place?" I answered that it was

the hustle and bustle of all the group activities of the camp--lots of

things going on with lots of people. "Make a maquette of that,"

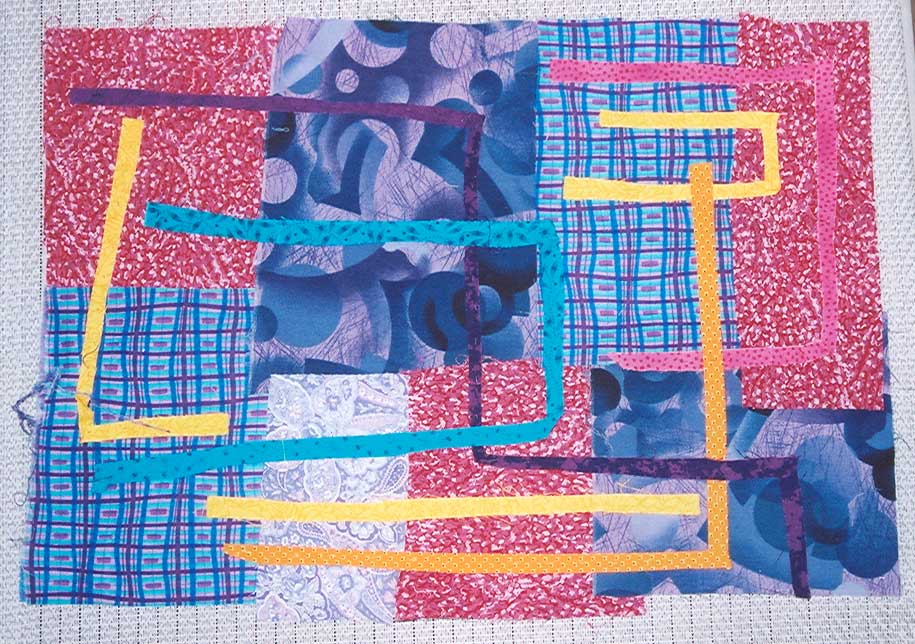

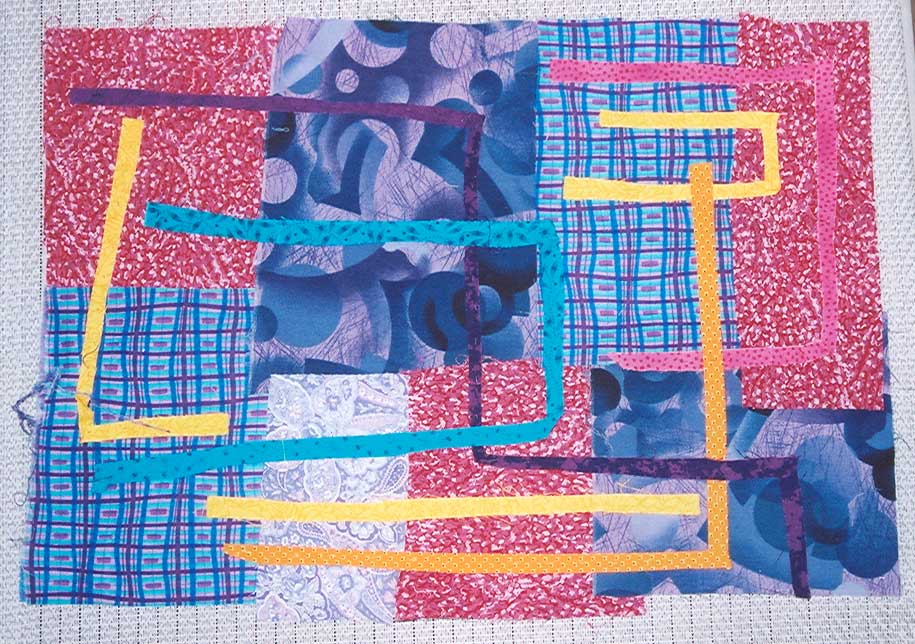

he said. So I did.

This one I was really happy with. I felt that I captured in color

and line some sense of what I was aiming for--the liveliness of the

usual camp day. "OK," said Bill, "Now go back to the pine grove."

And so I made this:

Yes, here it was, the feeling of the pine grove. Being able to

get to this abstract expression in the space of an hour or two--this

was amazing to me. I felt that something was unlocked, that I

could now do something I hadn't been able to do before--or that I had

reached into some well inside myself that I hadn't known was there.

The next day, after a morning talking about color, we were given

another exercise: to create a portrait. The goal of the exercise

was "to explore the power of color, so the portrait should not 'look

like' the person, but rather use color in an abstract way to represent

that person." To get started, they asked us to make a list of

words that came to mind when we thought of the person to be portrayed.

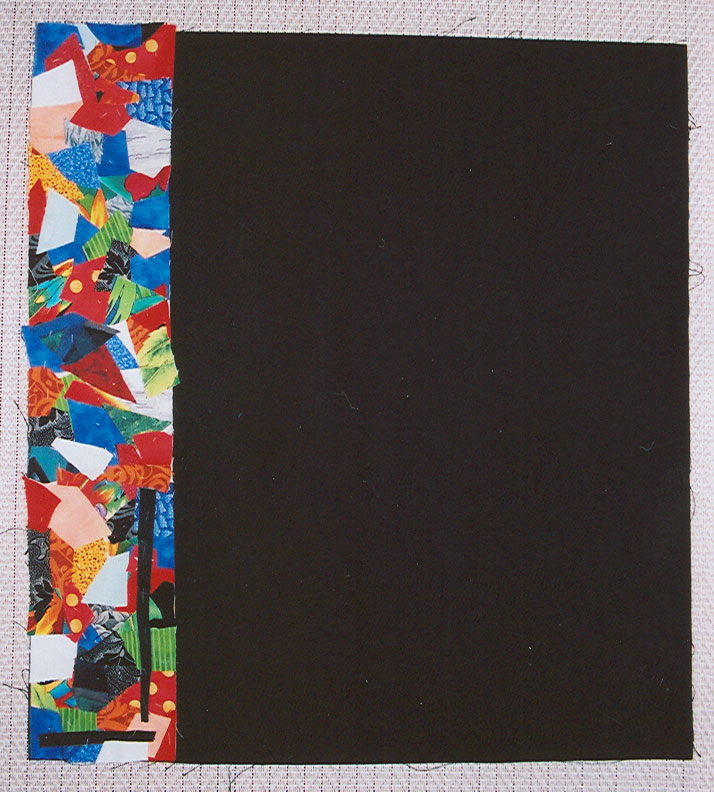

So here it was, an open door inviting me to work on a portrait of

Jeremy, something that would be the base for the multi-colored strip

in the sketch David and I had come up with:

Some of the words I wrote about Jeremy:

energetic

intense

sarcastic humor

shooting hoops

stubborn

moody

angry

And here's the portrait I did for this exercise.

This came to me spontaneously, without a struggle. It was what I

wanted it to be. It put something of Jeremy's character, and

about how David and I felt about Jeremy in our lives, into a visual

form. And although I didn't think through the colors and shapes

as I picked the fabric and cut it, the choices were easy because I had

in mind the central idea I wanted to express: that this was about

Jeremy, about his energy and intensity, about his sharp edges, about

the problems as well as the joys. That his life was varied, but

also limited. All this somehow achieved through color and shape.

The next day of the workshop we began on the quilt we wanted to design

at the workshop. Well launched on the quilt about Jeremy's life

and our loss, it was clear this is what I was meant to work on, not

midwestern landscape. With the maquette of the mosaic side of the

quilt already done, the rest of the design came readily, putting the

color of Jeremy's life next to the blackness of our future.

But there were many questions still of scale and size. The

colorful strip has to feel narrow--Jeremy's life cut short. I

tried making the horizontal dimension largest, but decided on vertical.

And how big for the whole quilt? It had to be on the large

size, something on the scale of a person. Should it be his

height, 5'8"? No, that was too literal, but something in that

range. I put up five feet of fabric on a wall, and that seemed

right. For the rest of the workshop, and then in the weeks

afterwards, I worked out other details. I did a dozen or so

trials of different methods of sewing the colored pieces onto the

strip. The only thing I knew for sure was that the strip with

colored pieces had to be hand-sewn--this was work I wanted to do in the

quiet of handwork, not by machine, and not with glue. But should the

edges be raw or turned under? If raw, should I allow the edges to

fray? How big should the pieces be? How much should they

overlap, if at all? And what about the expanse of black--how would

that be quilted? In the past, all these questions would have

frustrated me--I would have been frustrated that I didn't know the

"right" answer, that I didn't know what would look best, and that I

didn't know how to figure it out. But with this project, I felt

entirely different. I was content to just keep at it until I had

a method that felt right.

Here's the difference: In all the quilting I'd done previously,

I'd begun with a design made by someone else. For each of the

subsequent decisions--fabric, color and value, border, binding,

quilting--for each of these I had only the guidance of wanting to make

something that would look nice, perhaps even beautiful. But now,

with the help of the workshop, I had begun a quilt with an idea of my

own, an idea that I cared deeply about. For every decision I

faced, I had this idea to guide me. It wasn't a question of what

"looked best," but of what best conveyed the idea I wanted to express.

Bill and Weeks kept asking, "What's the big idea?" (This principle is certainly not unique to quilting. For an

example of a book that discusses this, as well as other principles of

creative work, I recommend Twyla Tharp's The Creative Habit.)

Somthing that happened this November really confirmed for me that I had

learned the lessons of the workshop. By early that month, when

I'd appliquéd about twelve inches of the colored strip for the

quilt, I stopped working on it. The design camp teachers were

having an open studio later in the month, an evening when any of their

students could bring in work in progress to talk about. I planned

to go to the session, so I thought it best to put aside the quilt for a

couple of weeks. That way, if talking with them led to a change

in design, I wouldn't have so much to re-do. But it didn't last

more than a couple of days. I couldn't stay away from the quilt,

from having this work under my hands. It was what I needed to be

doing. I realized that I already knew that how I was doing it was

just fine. I would be bringing the work into their studio because

I very much wanted them to see it, but not because I felt the need for

comments. It was the way I wanted it to be.

And so, now once again, the question, "Why Quilt?" I still have

pleasure, of course, in the simple doing of the handwork. And it

still helps me with a life of mourning. But I also now quilt in

order to bring out into the world an expression of something I feel,

something I can't put into words--even if I've tried to do so this

evening. I'm doing this for myself. It has been a very

private endeavor, and I don't feel entirely comfortable talking about

and showing this piece. When done, it's not something that will

be used on a bed or even hung on a wall. I suppose it's been a

kind of therapy. And it has also become art.

And one final possibility for answering the question "Why quilt?"

When I was at the design workshop, well along in working on the

quilt design, I brought the maquette over to Bill to ask him a

straightforward technical question. Oddly, he didn't respond.

When I asked again, he said, "Penny, it's not so easy for me to

look at this. I have my own losses too." It hadn't occurred

to me that something so personal, so specific, to me (and to David)

could also strike this kind of chord with another person. Perhaps

that's yet another reason to quilt.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Postscript: It took me another two and a half years to finish the quilt in its entirety: